April 21 | ![]() 0 COMMENTS

0 COMMENTS ![]() print

print

The search to find the face of the Lord

THE BOW IN THE HEAVENS looks at religious films, and how we all have different images of what Christ looks like — Fr JOHN BOLLAN

I’M not a huge fan of ‘religious’ movies. I remember being very disgruntled when my Mum got her friends from the Union of Catholic Mothers round to watch Franco Zeffirelli’s Jesus of Nazareth on Palm Sunday 1977, and I was made to watch that instead of a documentary on Doctor Who which was airing on BBC2 at the same time.

The fact I can still remember the date, April 3, should give you an idea of the mark it left on me. As the titles rolled and with tears in her eyes, I can still hear Mum say, ‘That makes you proud to be a Catholic.’ All her friends, fighting back their own tears, nodded in agreement.

My own tears of protest had long since dried, but I was still not prepared to join in the cooing over ‘Jesus’ lovely eyes’ and how Our Lady’s flawless complexion was obviously down to her being sinless.

Ever since then my relationship with dramatisations of the Gospels has been a little lukewarm: Pier Paolo Pasolini’s The Gospel According to St Matthew is certainly interesting and I’ve watched it several times, but I only managed to give Mel Gibson’s The Passion of the Christ one viewing.

To say I wouldn’t want to see it again is no particular criticism of the film itself: it’s something I’d recommend everyone should see—but once is probably enough for most people.

Last week I got around to watching not so much a film about the Gospel as a film about events parallel to it, the 2016 movie Risen. On the whole, I’d say it was actually quite a good film, certainly better than most of the reviews.

It takes a forensic approach to the Resurrection, approaching the empty tomb as both a crime scene and a policing issue for the Romans.

The investigating officer, a Roman tribune played by Joseph Fiennes, is out to find the stolen body of the so-called Christ. The tension created by rumours surrounding the disappearance of a corpse is ramped up by the imminent arrival of the emperor himself. That’s an example of artistic licence on the part of the film maker. By this time, the emperor Tiberius was living a debauched self-imposed exile on Capri, seldom visiting Rome itself never mind the troublesome backwater of Judea.

But these liberties aside, which would only really trouble a classicist with no mates, I must say I liked the film.

I thought it really conveyed a sense in which many of the events narrated in the Easter Gospels unfold in a pretty compressed timeline: we’re talking hours and days rather than several weeks (as we tend to hear them over the Easter season).

I also enjoyed the way it offered a Roman perspective on things, emphasising that the Resurrection—or even talk of it —was a massive pain for the empire. But most of all I liked the way in which the film’s central conceit—the search for the Risen Jesus—is also the basic thrust of the Christian life.

The Roman ‘detective’ has already seen Jesus die on the cross; at one point, he holds the shroud which had wrapped the missing body (the features clearly suggesting this is the Turin Shroud, by the way) and when he finally does see Jesus he has to do a double-take, the motion of the camera mimicking the surprise of encountering someone whom you plainly saw dead only a short while before.

As I said above, the basic orientation of the Christian life is the search for the Risen Lord. Moreover, we could say that it’s the search for his face. As Pope Benedict wrote in the introduction to his 2007 work Jesus of Nazareth, what he was offering in that book was ‘his own personal search for the face of the Lord.’

It so happens that I had been considering the very same thing in a book which was also published that same year (but a few months earlier, lest I be accused of plagiarism).

The Light of His Face was a pulling together of reflections and some resources principally intended for my students at Glasgow University.

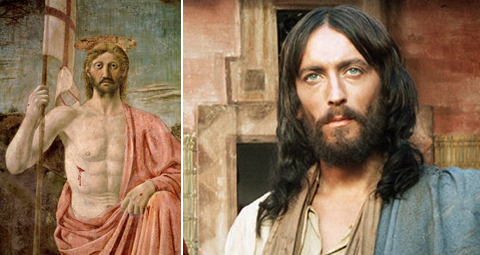

When I was asked to suggest or provide an image for the cover, I replied without hesitation that I would like a detail of the face of Christ from Piero della Francesca’s fresco of the Resurrection.

You can see it, still remarkably fresh after 550 years, painted on the wall of the old Town Hall of Borgo Sansepolcro, his birthplace in Tuscany.

I first saw it on the cover of a book which I had been given, somewhat mysteriously, as a prize by my P3 teacher Miss McEvaddy.

To this day, I’m not sure what the prize was for: she returned from her native Dublin after the Easter break bearing this translation of The Imitation of Christ by Thomas à Kempis and announced to the class that John Bollan had won this prize.

Quite what I was meant to make of this work of heavy-duty devotion, being still only six, was anybody’s guess.

It was perhaps due to the impenetrable language of the text that the image on the cover made all the more of an impression on me.

As I gazed at it in wonder, lots of synapses must have been firing in my wee brain, as this image became indelibly imprinted in my mind. More than any other, whenever I hear the name ‘Jesus,’ this is the face which answers the summons.

It is a face both beautiful and serene, an expression of gentle power as the Risen Christ steps up out of the tomb. The fact that ‘my’ face of Christ is that of the Risen Lord has inevitably come to shape my own spirituality: it is a thing of Easter.

Each of us has our own face of Jesus, of course: yours might be the Divine Mercy, or the Suffering Servant, or even Robert Powell’s Jesus of Nazareth. What matters is that we have an image which speaks to us and for us.

After the bustle of the Triduum, I have taken the opportunity to have a couple of days in Rome. Whenever parishioners hear you’re going to Rome, there’s always a heart-warming assumption that it’s ‘work-related.’

For years I used to exploit this, but now I just ‘fess up that the trip is mostly about wine drinking in Trastevere.

Any visit to the Eternal City shows up the split in my personality, between the priest and the Roman historian. While it’s a delight to visit some of the Roman basilicas arrayed in their Paschal glory, I’m just as at home among the ruins of the Forum or the Palatine hill. Oddly enough, it’s on the Palatine, the most sought-after district of ancient Rome where the emperors resided (our word ‘palace’ is derived from it) that we find one of the first images of Jesus.

Well, I say of Jesus but it’s actually of a donkey-headed man on a cross: it is a graffito scratched into the plaster in the imperial slave quarters, depicting a young man standing in an attitude of prayer before this crucified figure.

Below this scene is scrawled the caption ‘Alexamenos worships his god.’ Clearly Alexamenos was being mocked by his fellow slaves for his devotion to a crucified man, a thing surely worthy of mockery since people were still routinely being put to death on crosses in the valley below. So even my traipsing round pagan sites is a form of pilgrimage: alongside the emperors for whom the Nazarene was a threat to public order and harmony, we find traces of ordinary men and women who made no secret of their faith, even if it brought them derision or death.

In a sense, we should be grateful to whoever was bullying Alexamenos: we don’t know their names, but we do know his. The unlikely God he worshipped has had the last laugh.