January 10 | ![]() 0 COMMENTS

0 COMMENTS ![]() print

print

The meek will still inherit Earth

The relentless pursuit of economic self-interest is at odds with a life in Christ, writes Brandon McGinley in his letter from America.

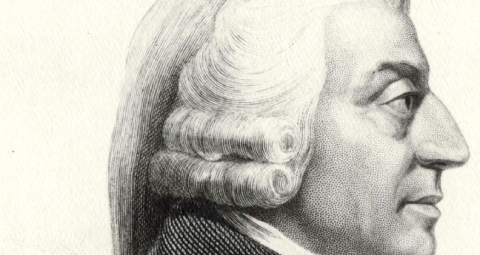

I don’t know if the concept of ‘self-interest’ was rehabilitated by the Scottish economist-philosopher Adam Smith all by himself, or if other lesser-known thinkers predated his elevation of avarice.

What I do know is that in the civilisation his laissez-faire economics helped to create, the ability to strategically pursue one’s self-interest is considered not just a virtue, but something like the baseline condition for being a rational human being.

Smith, a Glasgow University professor, himself would likely have been distressed by developments.

Though his elevation of self-interest is nakedly anti-Christian (whether he believed in anything like the God of the Bible is contested by historians), in his other work he allows that genuinely disinterested charity is both possible for people and good for society.

Self-interest

And yet here we are. As a civilisation we have taken to heart the idea that the aggressive pursuit of self-interest is not only essential to our humanity but essential to a thriving society. The fruits of economic inequality and social alienation are easy to see, but it’s all but impossible to imagine things being a

different way: The idea of genuine cooperation and charity is ruled out by our nearly religious devotion to the necessity of self-interest.

At the same time, no one has ever uttered the phrase: “I really admire that man as a Christian: He’s very effective at getting what he wants from others.” Connivance, manipulation, deceit—we all recognise the real actions men take to actualise their self-interest as vices, and not just any vices: These are vices that specifically contrast with the personality of Jesus and the spirit of His teaching.

We all know His words from the Sermon on the Mount: “I say to you, Do not resist one who is evil. But if anyone strikes you on the right cheek, turn to him the other also; and if anyone would sue you and take your coat, let him have your cloak as well; and if anyone forces you to go one mile, go with him two miles. (Matthew 5:39-40)

Contradiction

Any teaching of Christ, like this one, that so clearly contradicts the spirit of the age is one the Church should focus on in her public ministry and through the daily lives of the faithful. And we can know that this teaching is a particular sign of contradiction since the virtue it describes—meekness—is now considered to be a negative character trait.

In the tradition of the Church, meekness is a habit of the soul that restrains our anger from taking vengeance—even justifiable vengeance. We can extend this to include declining to make justifiable choices to advance our self-interest or to realise our preferences.

As a spiritual habit, this virtue inclines us to favour others’ feelings and interests ahead of our own. While it may not be the supreme virtue, it is perhaps, in the context of our culture of self-interest, the virtue that most clearly manifests the spirit of Christ.

Selflessness

Meekness, we must insist, is not weakness. First of all, like any virtue, it is difficult to acquire. It’s hard work to learn to put others first. We can start by, for instance, choosing the least desirable piece of pizza in the box—this is a lot harder than it sounds, trust me.

We can acquiesce to others’ preferences in restaurants or movies, provided they aren’t immoral. And we can show our children how to be meek by daring to be meek toward them, for instance by apologising when we have genuinely wronged them or by cheerfully playing boring-for-adults games with them.

Importantly, meekness does not require looking past wrongs done to those in our charge. Every virtue has related vices, and pusillanimity—also known as faintheartedness—is what happens when meekness does become weakness.

Honouring Christ

A virtuously meek disposition should never restrain us from taking a good but hard action for the benefit of another person, especially a child or other inferior. This does not honour Christ, either by imitating Him or by bringing His spirit of truth and fortitude to others.

In a genuine meekness, however, we demonstrate the grandness of Christ—His disregard for worldly respect and His willingness to be a sign of contradiction. There’s hardly any habit of soul we can cultivate that would more effectively build up His Kingdom in our days.

—Brandon McGinley is a writer living in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania