June 28 | ![]() 0 COMMENTS

0 COMMENTS ![]() print

print

Humour can be a unifying, healing force that bridges divides

Brandon McGinley finds laughter helps despite the troubles we face.

Heaven and hell are serious business. Souls are on the line every moment of every day. A single mortal sin breaks our relationship with God—permanently, if we refuse to accept His invitations to return to Him.

And a single kind word might be the hook God uses to pull a lost soul back to communion with Him and His Church.

When the stakes are this high, anything but a relentlessly grave disposition toward everyday life can seem frivolous and irresponsible. How can we justify lightheartedness when angels and demons are doing spiritual battle all around us for the eternal destiny of every soul?

And yet, at some level, we know this simply can’t be; we know there’s something inhuman about perpetual seriousness.

The killjoy, the sourpuss are types we all recognise, and we don’t find them attractive or enjoyable to be around. Even the trench soldier makes jokes: He has to, for his own sanity.

Why is that? Quite simply, it’s because human beings are neither angels nor automatons.

We cannot immediately and perfectly synthesise everything that’s happening in the physical and spiritual world, and then analyse it all dispassionately. We are mortal and limited beings; we can’t focus single-mindedly on any one aspect of life in perpetuity.

Humour

Enter humour, which is one of the distinctively and essentially human ways we divert ourselves from the serious, the solemn, the practical. We laugh, even about serious matters, not in order to spurn eternity or divinity, but as part of embracing the often ridiculous reality of our humanity.

Irony, surprise, blunder, misapprehension—these are part of being human and, provided we remember and respect the dignity of everyone involved, they are often funny.

And they don’t stop being natural or funny in serious times. In fact, the value of humour—genuine humour, not mockery or derision or other forms of cruelty—is all the higher in times when troubles and

anxieties seem to be everywhere. This is true not just in the world, but specifically in the Church.

While there are corners of the Church more embroiled in crisis and scandal than my own, there probably aren’t too many.

Last year the state of Pennsylvania released an official report on the history of clergy sex abuse in my diocese, revealing roughly the same magnitude of crimes and cover-ups as other major American sees.

This happened in the midst of a massive reorganisation of the diocese, with every parish merging with at least one neighbour and dozens of church buildings slated to close.

Sharks are circling for payouts (there are exploitative billboards around the city advertising attorneys who can raid the diocesan abuse fund) and donations are down. It may take a generation or more for the diocese to regain its footing, financially and pastorally.

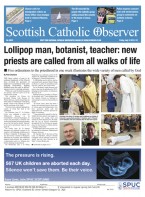

This is a time for prayer and serious thinking about the future—but it’s also exactly the time for the balm of humour. An enterprising pastor in my diocese recognised this and invited an up-and-coming Catholic comedian, Jeremy McLellan (above), to do a show at his large parish.

McLellan, a recent convert, intuitively understands the things that make the Church funny in a way recognisable to but often forgotten by more established Catholics in this era of anxiety and crisis.

His humour is dignified and respectful while remaining strategically transgressive and, well, hilarious.

McLellan’s show was a hit; even if every joke didn’t hit every audience member’s sweet spot (they never all do), there was a palpable sense in the room that this kind of controlled and cheerful catharsis had been good and necessary.

Humour within an in-group, like Catholics, can be uniquely unifying, reminding us of our eccentricities and shared experiences of ecclesial irony and blunder.

Reconciliation

It has been said (perhaps by St Francis de Sales?) that humour is the foundation of reconciliation.

We can broaden this to say: humour is an example of something shared, a point of contact among persons, that allows for the process of reconciliation to begin.

If we can agree to laugh together, especially about shared experiences, then maybe we can agree to talk together.

In these hard times in the world and the Church, let’s remember to laugh—to recognise what’s genuinely funny, to embrace our mirth, and to share it with others.

Humour won’t save the world from sin, but it may save it from dourness—and that’s a step in the right direction.