April 12 | ![]() 0 COMMENTS

0 COMMENTS ![]() print

print

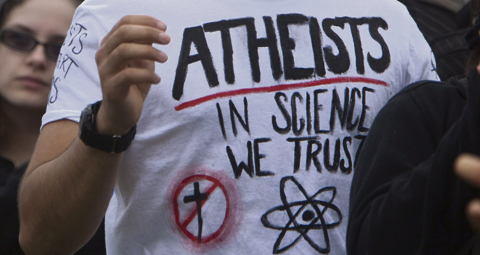

The ongoing struggle with secularity

Fr Ronald Rolheiser

We live in a highly secularised culture. Generally, this draws one of three reactions from Christians struggling to live out faith in this context.

First, a growing number of Christians of all denominations see secularity more as an enemy of faith and the churches than as an ally. In their view, secularity is a threat to religion and morality and is, in the name of freedom and open-mindedness, slowly suffocating Christian freedom. For them, secularity contains within itself a certain tyranny of relativism which can aptly be labelled ‘post-Christian’ and ‘a culture of death.’

A second group simply accommodates itself to the culture without a lot of critical reflection either way. They adjust the faith to the culture and the culture to the faith as suits their situation. For them, faith becomes largely a cultural heritage, an ethos more than a religion, though this is not as much of a blind sell-out as it first appears. Deeper struggles go on beneath, prompted not just by the soul’s perennial questions but also by the Judeo-Christian genes inside the DNA of both the culture and the individual. So these individuals selectively take values from both the Judeo-Christian tradition and the secular culture and blend them into a new marriage, seemingly without a lot of religious anxiety.

A third group has a more nuanced approach: Persons such as Charles Taylor, Louis Dupré, Kathleen Norris, and, a generation earlier, Karl Rahner, see secularity as a mixed bag, a culture of both life and death, a culture that in some ways is a progression in and a purification of moral and religious values, even as it is losing ground morally and religiously in other ways. Of major importance in this view is the idea that secular culture, secularity, is the child of Judaism and Christianity. Judeo-Christianity, at least for the most part, gave birth to René Descartes, the principles of the Enlightenment, the French revolution, the Scottish revolution, the American revolution, and thus to democracy, the separation of church and state, and the principle that so much undergirds secularity, namely, that we agree to organise public life on the principle of rational consensus rather than on the basis of divine authority—allowing, of course, for divine authority to influence rational consensus.

In this view, the opposite of secularity is not the church, but the Taliban or any view that holds that public life should be governed by divine authority irrespective of rational consensus. Secularity then is more our child than our enemy. However, if that is true, then why is secularity often so bitter and overly-critical in its attitude towards the Christian churches? This can seem like a contradiction, but secularity can be anti-Christian for the same reason that adolescents can be bitter and overly-critical towards their own parents, namely, adolescence is often immature and grandiose. But an immature, grandiose adolescent isn’t a bad person, just an unfinished one.

Viewing secularity from this perspective, it is equally important to highlight both the moral and religious ground that has been lost in secularity as well as the moral and religious ground that has been gained. Both can be seen, for example, by looking a highly secularised culture like the Netherlands: On one hand, it is very weak in church attendance and in explicit Christian practice. Along with this there is the tolerance and legalisation of abortion, drugs, prostitution, and pornography. On the other hand, they are a society that takes care of its poor better than any other society in the world and one that is recognised for its emphasis on generosity, peace, and the equality of women. These are not minor religious and moral achievements.

Where do I stand? Mostly with this third group and its belief that secularity is not our enemy but our child and that it carries inside itself both highly generative streams of life and asphyxiating rivulets of death. On one hand, I draw a lot of my life and joy from its creativity, colour, exuberance, and generative energy, often times against my own Germanic-propensity for greyness and acedia. I am also uplifted on a regular basis by the real generosity and genuine goodness that I find in most people I meet. Importantly too, I reap its stunning benefits—freedom, protection of my rights, privacy, opportunity for education, wonderful medical care, information technology, access to information, wide cultural and recreational opportunities, clean water, plentiful food, and, not least, the freedom to practise my Faith and religion.

On the negative side, I recognise too its elements of death: The tolerance of abortion, the marginalisation of the poor, the itch for euthanasia, lingering racism, widespread sexual irresponsibility, a growing addiction to pornography, and an ever-growing trivialisation and superficiality. As reality television becomes more indicative of our culture, I begin to despair more for its depth.

As an adult child of René Descartes, I breathe in secularity, a very mixed air, pure and polluted; and I find myself torn between hope and fear, comfortable but uneasy, defending secularity even as I am critical of it.

n Ronald Rolheiser, a Catholic priest and member of the Missionary Oblates of Mary Immaculate, is president of

the Oblate School of Theology in San Antonio, Texas