March 4 | ![]() 0 COMMENTS

0 COMMENTS ![]() print

print

Pope Benedict XVI’s Easter Story

The Scottish Catholic Observer offers a preview of Jesus of Nazareth—Holy Week with extracts from the book this week and next.

Four years after publishing his first acclaimed portrait of Jesus of Nazareth, Pope Benedict XVI returns to his theme.

Recognised by scholars as one of the most learned and respected theologians in the Catholic Church, the Holy Father guides the reader through the Easter story in his new book and reveals the person and mission of Jesus.

Following on for the critically acclaim of Jesus of Nazareth—From the Baptism in the Jordan to the Transfiguration, the Holy Father’s new book Jesus of Nazareth—Holy Week: From the Entrance into Jerusalem to the Resurrection will published in the UK on March 10 by the Catholic Truth Society.

“Only in this second volume do we encounter the decisive sayings and events of Jesus’s life,” Pope Benedict said. “I hope that I have been granted an insight into the figure of Our Lord that can be helpful to all readers who seek to encounter Jesus and to believe in Him.”

In the new book the Pope offers a meditation on the person of Jesus from His triumphant entrance into Jerusalem on the back of a donkey until His Resurrection, a brief and shockingly dramatic period encompassing the Last Supper, the agony in the Garden of Gethsemane, the betrayal by Judas Iscariot and the trial, torture and crucifixion.

He touches on difficult topics, such as the question of where the responsibility for the death of Jesus lies and debates questions such as: Was Jesus a political revolutionary or a prophet whose message has been distorted?; When Jesus prayed for unity among Christians what did he mean?; Can religious violence ever be justified?

“Pope Benedict’s new book offers a profound reflection on the meaning of the death of Jesus Christ,” Archbishop Kevin McDonald, Archbishop Emeritus of Southwark, Chairman of the Catholic Bishops’ Committee for Catholic Jewish Relations said.

“It provides a very fertile preparation for the celebration of Holy Week.

“As far as the Jewish question is concerned, it is important to see these reflections against the background of the very positive approach that the Pope has adopted to Catholic-Jewish dialogue both in his words and deeds.”

Senior clergy within the Church have suggested that readers should view the book as having been written by the theologian Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, and not by Pope Benedict XVI.

“This distinction is not a matter of splitting hairs,” said Cardinal Georges Cottier, the former theologian of the Papal household.

He added that even if it may be confusing in the case of Pope Benedict, a renowned theologian before being elected Pope, it is important for people to understand that theology is a human exercise, which is open to debate and criticism. The cardinal went on to say that, because of the Holy Spirit’s gift to the Church and to the individual elected, the teaching of a Pope requires a greater degree of assent.

– http://www.cts-online.org.uk

Jesus before Pilate (extract from Chapter 7)

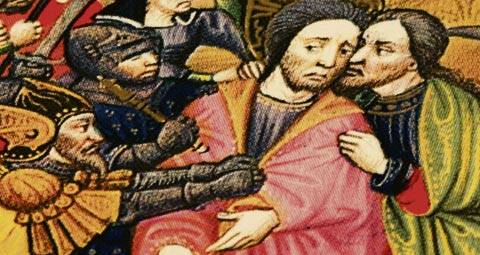

Jesus’ interrogation before the Sanhedrin had concluded in the way Caiaphas had expected: Jesus was found guilty of blasphemy, for which the penalty was death. But since only the Romans could carry out the death sentence, the case now had to be brought before Pilate and the political dimension of the guilty verdict had to be emphasised. Jesus had declared Himself to be the Messiah, hence He had laid claim to the dignity of kingship, albeit in a way peculiarly His own. The claim to Messianic kingship was a political offence, one that had to be punished by Roman justice. With cockcrow, daybreak had arrived. The Roman Governor used to hold court early in the morning.

So Jesus is now led by his accusers to the Praetorium and is presented to Pilate as a criminal who deserves to die. It is the ‘day of preparation’ for the Passover feast. The lambs are slaughtered in the afternoon for the evening meal. Hence cultic purity must be preserved; so the priestly accusers may not enter the Gentile Praetorium and they negotiate with the Roman Governor outside the building. John, who provides this detail (18:28f.), thereby highlights the contradiction between the scrupulous attitude to regulations for cultic purity and the question of real inner purity: it simply does not occur to Jesus’ accusers that impurity does not come from entering a Gentile house, but rather from the inner disposition of the heart. At the same time the evangelist emphasizes that the Passover meal had not yet taken place and that the slaughter of the lambs was still to come.

In all essentials, the four Gospels harmonise with one another in their accounts of the progress of the trial. Only John reports the conversation between Jesus and Pilate, in which the question about Jesus’ kingship, the reason for His death, is explored in depth (18:33-38). The historicity of this tradition is of course contested by exegetes. While Charles H. Dodd and Raymond E Brown judge it positively, Charles K Barrett is extremely critical: “John’s additions and alterations do not inspire confidence in his historical reliability” (The Gospel According to Saint John, p 530). Certainly no one would claim that John set out to provide anything resembling a transcript of the trial. Yet we may assume that he was able to explain with great precision the core question at issue, and that he presents us with a true account of the trial. Barrett also says ‘that John has with keen insight picked out the key of the Passion narrative in the kingship of Jesus, and has made its meaning clearer, perhaps, than any other New Testament writer’ (ibid, p. 531).

Now we must ask: who exactly were Jesus’ accusers? Who insisted that he be condemned to death? We must take note of the different answers that the Gospels give to this question. According to John it was simply ‘the Jews.’ But John’s use of this expression does not in any way indicate—as the modern reader might suppose—the people of Israel in general, even less is it ‘racist’ in character. After all, John himself was ethnically a Jew, as were Jesus and all His followers. The entire early Christian community was made up of Jews. In John’s Gospel this word has a precise and clearly defined meaning: he is referring to the Temple aritocracy. So the circle of accusers who instigate Jesus’ death is precisely indicated in the Fourth Gospel and clearly limited: it is the Temple aristocracy—and not without certain exceptions, as the reference to Nicodemus (7:50ff.) shows.

In Mark’s Gospel, the circle of accusers is broadened in the context of the Passover amnesty (Barabbas or Jesus): the ochlos enters the scene and opts for the release of Barabbas. Ochlos in the first instance simply means a crowd of people, the ‘masses.’ The word frequently has a pejorative connotation, meaning ‘mob.’ In any event it does not refer to the Jewish people as such. In the case of the Passover amnesty (which admittedly is not attested in other sources, but even so need not be doubted), the people, as so often with such amnesties, have a right to put forward a proposal, expressed by way of ‘acclamatio.’ Popular acclamation in this case has juridical character (cf Pesch, Markusevangelium, ii, p. 466). Effectively this ‘crowd’ is made up of the followers of Barabbas who have been mobilised to secure the amnesty for him: as a rebel against Roman power he could naturally count on a good number of supporters. So the Barabbas party, the ‘crowd.’ was conspicuous while the followers of Jesus remained hidden out of fear; this meant that the vox populi, on which Roman law was built, was represented one-sidedly. In Mark’s account, then, as well as ‘the Jews,’ that is to say the dominant priestly circle, the ochlos comes into play, the circle of Barabbas’ supporters, but not the Jewish people as such.

An extension of Mark’s ochlos, with fateful consequences, is found in Matthew’s account (27:25) which speaks of the ‘whole people’ and attributes to them the demand for Jesus’ crucifixion. Matthew is certainly not recounting historical fact here: how could the whole people have been present at this moment to clamour for Jesus’ death? It seems obvious that the historical reality is correctly described in John’s account and in Mark’s. The real group of accusers are the current Temple authorities, joined in the context of the Passover amnesty by the ‘crowd’ of Barabbas’ supporters.

Here we may agree with Joachim Gnilka, who argues that Matthew, going beyond historical considerations, is attempting a theological etiology with which to account for the terrible fate of the people of Israel in the Jewish War, when land, city and Temple were taken from them (cf Matthäusevangelium, ii, p 459). Matthew is thinking here of Jesus’ prophecy concerning the end of the Temple: “O Jerusalem, Jerusalem, killing the prophets and stoning those who are sent to you! How often would I have gathered your children together as a hen gathers her brood under her wings, and you would not! Behold, your house is forsaken …” (Mt 23:37f.: cf. Gnilka, the whole of the section entitled “Gerichtsworte”, pp 295-308).

These words—as argued earlier, in the chapter on Jesus’ eschatological discourse—remind us of the inner similarity between the Prophet Jeremiah’s message and that of Jesus. Jeremiah—against the blindness of the then dominant circles—prophesied the destruction of the Temple and Israel’s exile. But he also spoke of a ‘new Covenant’: punishment is not the last word, it leads to healing. In the same way Jesus prophesies the ‘deserted house and proceeds to offer the new Covenant ‘in His blood’: ultimately it is a question of healing, not of destruction and rejection.

When in Matthew’s account the ‘whole people’ say: ‘His blood be on us and on our children’ (27:25), the Christian will remember that Jesus’ blood speaks a different language from the blood of Abel (Heb 12:24): it does not cry out for vengeance and punishment, it brings reconciliation. It is not poured out against anyone, it is poured out for many, for all. “All have sinned and fall short of the glory of God … God put [Jesus] forward as an expiation by his blood” (Rom 3:23, 25). Just as Caiaphas’ words about the need for Jesus’ death have to be read in an entirely new light from the perspective of faith, the same applies to Matthew’s reference to blood: read in the light of faith, it means that we all stand in need of the purifying power of love which is His blood. These words are not a curse, but rather redemption, salvation. Only when understood in terms of the theology of the Last Supper and the Cross, drawn from the whole of the New Testament, does this verse from Matthew’s Gospel take on its correct meaning.

Let us move now from the accusers to the judge: the Roman Governor Pontius Pilate. While Flavius Josephus and especially Philo of Alexandria paint a rather negative picture of him, other sources portray him as decisive, pragmatic and realistic. It is often said that the Gospels presented him in an increasingly positive light out of a politically motivated pro-Roman tendency, and that they shifted the blame for Jesus’ death more and more onto the Jews. Yet there were no grounds for any such tendency in the historical circumstances of the evangelists: by the time the Gospels were written, Nero’s persecution had already revealed the cruel side of the Roman State and the great arbitrariness of imperial power. If we may date the Book of Revelation to approximately the same period as John’s Gospel, then it is clear that the Fourth Gospel did not come to be written in a context which could have given rise to a pro-Roman stance.

The image of Pilate in the Gospels presents the Roman Prefect quite realistically as a man who could be brutal when he judged this to be in the interests of public order. Yet he also knew that Rome owed its world dominance not least to its tolerance of foreign divinities and to the capacity of Roman law to build peace. This is how he comes across to us during Jesus’ trial.

The charge that Jesus claimed to be king of the Jews was a serious one. Rome had no difficulty in recognising regional kings like Herod, but they had to be legitimated by Rome and they had to receive from Rome the definition and limitation of their sovereignty. A king without such legitimation was a rebel who threatened the Pax Romana and therefore had to be put to death.

Pilate knew, however, that no rebel uprising had been instigated by Jesus. Everything he had heard must have made Jesus seem to him like a religious fanatic, who may have offended against some Jewish legal and religious rulings, but that was of no concern to him. The Jews themselves would have to judge that. From the point of view of the Roman juridical and political order, which fell under his competence, there was nothing serious to hold against Jesus.

At this point we must pass from considerations about the person of Pilate to the trial itself. In Jn 18:34f. it is clearly stated that, on the basis of the information in his possession, Pilate had nothing that would incriminate Jesus. Nothing had come to the knowledge of the Roman authority that could in any way have posed a risk to law and order. The charge came from Jesus’ own people, from the Temple authority. It must have astonished Pilate that Jesus’ own people presented themselves to him as defenders of Rome, when the information at his disposal did not suggest the need for any action on his part.

Yet during the interrogation we suddenly arrive at a dramatic moment: Jesus’ confession. To Pilate’s question: “So you are a king?” he answers: “You say that I am a king. For this I was born, and for this I have come into the world, to bear witness to the truth. Every one who is of the truth hears my voice” (Jn 18:37). Previously Jesus had said: “My kingship is not of this world; if my kingship were of this world, my servants would fight, that I might not be handed over to the Jews; but my kingship is not from the world” (18:36).

This ‘confession’ of Jesus places Pilate in an extraordinary situation: the accused claims kingship and a kingdom (basileia). Yet he underlines the complete otherness of his kingship, and he even makes the particular point that must have been decisive for the Roman judge: no one is fighting for this kingship. If power, indeed military power, is characteristic of kingship and kingdoms, there is no sign of it in Jesus’ case. And neither is there any threat to Roman order. This kingdom is powerless. It has ‘no divisions.’

With these words Jesus created a thoroughly new concept of kingship and kingdom, and he held it up to Pilate, the representative of classical worldly power. What is Pilate to make of it, and what are we to make of it, this concept of kingdom and kingship? Is it unreal, is it sheer fantasy, that can be safely ignored? Or does it somehow affect us?

In addition to the clear delimitation of his concept of kingdom (no fighting, earthly powerlessness), Jesus had introduced a positive idea, in order to explain the nature and particular character of the power of this kingship: namely truth. Pilate brought another idea into play as the dialogue proceeded, one that came from his own world and was normally connected with ‘kingdom:’ namely power – authority (exousía). Dominion demands power, it even defines it. Jesus, however, defines as the essence of his kingship witness to the truth. Is truth a political category? Or has Jesus’ ‘kingdom’ nothing to do with politics? To which order does it belong? If Jesus bases His concept of kingship and kingdom on truth as the fundamental category, then it is entirely understandable that the pragmatic Pilate asks Him: “What is truth?” (18:38).

It is the question that is also asked by modern political theory: can politics accept truth as a structural category? Or must truth, as something unattainable, be relegated to the subjective sphere, its place taken by an attempt to build peace and justice using whatever instruments are available to power? By relying on truth, does not politics, in view of the impossibility of attaining consensus on truth, make itself a tool of particular traditions which in reality are merely forms of holding on to power?

And yet on the other hand, what happens when truth counts for nothing? What kind of justice is then possible? Must there not be common criteria, which guarantee real justice for all—criteria that are independent of the arbitrariness of changing opinions and powerful lobbies? Is it not true that the great dictatorships were fed by the power of the ideological lie, and that only truth was capable of bringing freedom?

What is truth? The pragmatist’s question, tossed off with a degree of scepticism, is a very serious question, bound up with the fate of humanity. What, then, is truth? Are we able to recognise it? Can it serve as a criterion for our intellect and will, both in individual choices and in the life of the community?

The classic definition from scholastic philosophy designates truth as ‘adaequatio intellectus et rei – conformity between the intellect and reality’ (Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologiae, I q 21 a. 2c). If a man’s intellect reflects a thing as it is in itself, then he has found truth: but only a small fragment of reality—not truth in its grandeur and integrity.

We come closer to what Jesus meant with another of Saint Thomas’s teachings: “Truth is in God’s intellect properly and firstly (proprie et primo); in human intellect it is present properly and derivatively (proprie quidem et secundario)” (De verit q 1 a. 4c). And in conclusion we arrive at the succinct formula: God is ‘ipsa summa et prima veritas: truth itself, the sovereign and first truth’ (Summa Theologiae, I q 16 a. 5c).

This formula brings us close to what Jesus means when He speaks of the truth, when He says that His purpose in coming into the world was to ‘bear witness to the truth.’ Again and again in the world, truth and error, truth and untruth, are almost irretrievably mixed together. The truth in all its grandeur and purity, does not appear. The world is ‘true’ to the extent that it reflects God: the creative logic, the eternal reason that brought it to birth. And it becomes more and more true the closer it draws to God. Man becomes true, he becomes himself, when he grows in God’s likeness. Then he attains to his proper nature. God is the reality that gives being and intelligibility.

‘Bearing witness to the truth’ means giving priority to God and to his will over against the interests of the world and its powers. God is the criterion of being. In this sense truth is the real ‘king’ that confers light and greatness upon all things. We may also say that bearing witness to the truth means making creation intelligible and its truth accessible from God’s perspective—the perspective of creative reason—in such a way that it can serve as a criterion and a signpost in this world of ours, in such a way that the great and the mighty are exposed to the power of truth, the common law, the law of truth.

Let us say plainly: the unredeemed state of the world consists precisely in the failure to understand the meaning of creation, in the failure to recognize truth; as a result the rule of pragmatism is imposed, by which the strong arm of the powerful becomes the god of this world.

At this point, modern man is tempted to say: creation has become intelligible to us through science. Indeed, Francis S Collins, for example, who led the Human Genome Project, says with joyful astonishment: “The language of God was revealed” (The Language of God, p 122). Indeed, in the magnificent mathematics of creation, which today we can read in the human genetic code, we recognise the language of God. But unfortunately not the whole language. The functional truth about man has been discovered. But the truth about man himself—who he is, where he comes from, what he should do, what is right, what is wrong—this unfortunately cannot be read in the same way. Hand in hand with growing knowledge of functional truth there seems to be an increasing blindness towards ‘truth’ itself – towards the question of our real identity and purpose.

What is truth? Pilate was not alone in dismissing this question as unanswerable and irrelevant for his purposes. Today too, in political argument and in discussion of the foundations of law, it is generally experienced as disturbing. Yet if man lives without truth, life passes him by, ultimately the field is surrendered to whoever is the stronger. ‘Redemption’ in the fullest sense can only consist in the truth becoming recognisable. And it becomes recognisable when God becomes recognisable. He becomes recognisable in Jesus Christ. In Christ, God entered the world and set up the criterion of truth in the midst of history. Truth is outwardly powerless in the world, just as Christ is powerless by the world’s standards: He has no divisions, He is crucified. Yet in His very powerlessness, He is powerful: only thus, again and again, does truth become power.

The Mystery of the Betrayer (extract from Chapter 3)

The account of the washing of the feet presents us with two different human responses to this gift, exemplified by Judas and Peter. Immediately after the exhortation to follow his example, Jesus begins to speak of Judas. John tells us in this regard that Jesus was troubled in spirit and testified: “Truly, truly, I say to you, one of you will betray me” (13:21).

John speaks three times of Jesus’ being ‘troubled’: beside the grave of Lazarus (11:33, 38), on ‘Palm Sunday’ after the saying about the dying wheat-grain in a scene reminiscent of Gethsemane (12:24-27), and finally here. These are moments when Jesus encounters the majesty of death and rubs against the might of darkness, which it is his task to wrestle with and overcome. We shall return to this ‘troubling’ of Jesus’ spirit when we consider the night spent on the Mount of Olives.

Let us return to our text. Understandably, the prophecy of the betrayal produces agitation and curiosity among the disciples. “One of His disciples, whom Jesus loved, was lying close to the breast of Jesus: so Simon Peter beckoned to him and said, ‘Tell us who it is of whom He speaks.’ So lying thus, close to the breast of Jesus, he said to Him: ‘Lord, who is it?’ Jesus answered: ‘It is he to whom I shall give this morsel when I have dipped it’” (13:23ff).

In order to understand this text, it should be noted first of all that reclining at table was prescribed for the Passover meal. Charles K Barrett explains the verse just quoted as follows: “Persons taking part in a meal reclined on the left side; the left arm was used to support the body, the right was free for use. The disciple to the right of Jesus would thus find his head immediately in front of Jesus and might accordingly be said to lie in his bosom. Evidently he would be in a position to speak intimately with Jesus, but his was not the place of greatest honour; this was to the left of the host. The place occupied by the beloved disciple was nevertheless the place of a trusted friend”; Barrett then makes reference to a passage from Pliny (The Gospel According to Saint John, p. 446).

Jesus’ answer, as given here, is quite unambiguous. Yet the evangelist says that the disciples still did not understand who He meant. So we must assume that John retrospectively attributed a clarity to the Lord’s answer that it lacked at the time for those present. Verse 18 brings us onto the right track. Here Jesus says: “The Scripture must be fulfilled: ‘He who ate my bread has lifted his heel against me’” (cf Ps 41:10; Ps. 55:14). This is Jesus’ classic way of speaking: He alludes to His destiny using words from Scripture, thereby locating it directly within God’s logic, within the logic of salvation history.

At a later stage, these words become fully transparent; it is seen that Scripture really does describe the path He is to tread—but for now the enigma remains. All that can be deduced at this point is that one of those at table will betray Jesus; it is clear that the Lord will have to endure to the end and to the last detail the suffering of the just, for which the psalms in particular provide many different expressions. Jesus must experience the incomprehension and the infidelity even of those within his innermost circle of friends, and in this way ‘fulfil the Scripture.’ He is revealed as the true subject of the psalms, the ‘David’ from whom they come and through whom they acquire meaning.

John gives a new twist to the psalm verse with which Jesus spoke prophetically of what lay ahead, since instead of the expression given in the Greek Bible for ‘eating,’ he chooses the verb trōgein, the word used by Jesus in the great ‘bread of life’ discourse for ‘eating’ His flesh and blood, ie receiving the sacrament of the Eucharist (Jn 6:54-58). So the psalm verse casts a prophetic shadow over the Church of the evangelist’s own day in which the Eucharist was celebrated, and indeed over the Church of all times: Judas’ betrayal was not the last breach of fidelity that Jesus would suffer. “Even my friend, in whom I trusted, who ate my bread, has turned against me” (Ps 41:10). The breach of friendship extends into the sacramental community of the Church, where people continue to take ‘His bread’ and to betray Him.

Jesus’ agony, His struggle against death, continues until the end of the world, as Blaise Pascal said on the basis of similar considerations (cf. Pensées VII:553). We could also put it the other way round: at this hour, Jesus took upon himself the betrayal of all ages, the pain caused by betrayal in every era, and he endured the anguish of history to the bitter end.

John does not offer any psychological interpretation of Judas’ conduct. The only clue he gives is a hint that Judas had helped himself to the contents of the disciples’ money-box, of which he had charge (12:6). In the context of Chapter 13, the evangelist merely says laconically: “Then after the morsel, Satan entered into him” (13:27).

For John, what happened to Judas is beyond psychological explanation. He has come under the dominion of another. Anyone who breaks off friendship with Jesus, casting off his ‘easy yoke,’ does not attain liberty, does not become free, but succumbs to other powers. To put it another way, he betrays this friendship because he is in the grip of another power to which he has opened himself.

True, the light shed by Jesus into Judas’ soul was not completely extinguished. He does take a step towards conversion: “I have sinned,” he says to those who commissioned him. He tries to save Jesus, and he gives the money back (Mt 27:3ff.). Everything pure and great that he had received from Jesus remained inscribed on his soul—he could not forget it.

His second tragedy—after the betrayal—is that he can no longer believe in forgiveness. His remorse turns into despair. Now he sees only himself and his darkness, he no longer sees the light of Jesus that can illumine and overcome the darkness. He shows us the wrong type of remorse: the type that is unable to hope, that sees only its own darkness, the type that is destructive and in no way authentic. Genuine remorse is marked by the certainty of hope born of faith in the superior power of the light that was made flesh in Jesus.

John concludes the passage about Judas with these dramatic words: “after receiving the morsel, he immediately went out; and it was night” (13:30). Judas goes out—in a deeper sense. He goes into the night, he moves out of light into darkness: the ‘power of darkness’ has taken hold of him (cf Jn 3:19; Lk 22:53).