November 29 | ![]() 0 COMMENTS

0 COMMENTS ![]() print

print

The deeper significance of Lisbon Lions’ win for Scotland’s Catholic community of Irish descent

More than half a century after the Bhoys’ historic European Cup victory in Lisbon, Dr Joseph Bradley and Dr John Kelly examine its deeper significance for Scotland’s Irish Catholic community

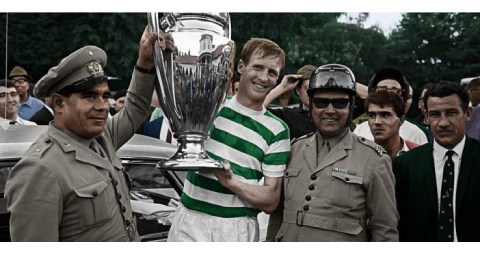

On May 25, 1967, in the Portuguese capital of Lisbon, Celtic Football Club defeated Internazionale from Milan 2-1 to become the first club from Britain and, indeed, the first from northern Europe to win the European Cup. By 2019, barely 22 clubs have managed to win this most prestigious of football trophies.

Moreover, Celtic’s win originated from much more modest and humble beginings than those of any other club to achieve this sporting success.

Despite Celtic’s win being reported widely and documented regularly throughout the years, the overwhelming majority of such discourse has considerably overlooked the magnitude and iconographic significance of this defining socio-cultural moment when 15,000 supporters, mainly from Scotland, travelled to Portugal to watch their team in the final.

Iconic status

One popular historian records a revealing, but passing comment on how so many of the Celtic supporters attended the celebration of Catholic Mass on the day of the final, at Lisbon’s Estadio Nacional. Apart from this reference to Catholic Celtic supporters attending Mass (a few also visited the Shrine to Our Lady at Fatima en route) little of this account distinguishes Celtic’s win from those of other sides from Britain during the following decades. Despite all the histories written about the club’s win, the iconic status claimed and presumed is rarely explored and articulated.

That is, the deep and profound impact this victory represents for many Celtic supporters—in ethnic, community and religious terms: indeed, these are conspicuous by their absence.

One contemporary and much lauded account of Celtic’s European Cup victory justifiably describes Celtic’s win as ‘absolutely fantastic’. However, the iconic nature of the win as a defining moment of sociocultural significance is reduced to being simply proclaimed as a ‘Scottish victory’ and to being ‘the first British side’ to lift the European Cup. Indeed, when captain Billy McNeill died last year, this phrase featured in many obituaries.

Colonialism

Nonetheless, from the embers of colonialism, mass starvation and Irish Catholic immigration from Ireland to Scotland flickered the flame of a diaspora negotiating and forming its identity in Scotland: and from 1888 until today, Celtic Football Club has been one of their most revered totems. Fifty years after the event, the enormity of Celtic’s achievement was recalled by the historian Professor Tom Devine who encapsulated the extraordinary significance of the win in Lisbon for Catholics of Irish immigrant descent in Scotland, suggesting that 1967 represented: A key factor in the long story of the emancipation of the Catholic Irish in this country [Scotland]… in terms of signal events, the Lisbon Lions victory probably stands alongside the visit of Pope John Paul II in 1982.

Celtic’s origins begin with the cataclysmic mass death-dealing Great Starvation (An Gorta Mor) in Ireland, when millions of people died or were forced to flee a colonised island. One of this event’s main consequences for Scotland was that Irish Catholic immigration led to the foundation, development and establishment of Celtic FC. The main purpose in the club’s

formation was explained in a circular issued in January 1888: The main object of the club is to supply the East End conferences of the St Vincent de Paul Society with the funds for the maintenance of the ‘dinner tables’ of our needy children in the missions of St Mary’s, Sacred Heart and St Michael’s. Many cases of sheer poverty are left unaided through lack of means. It is therefore with this object that we have set afloat the ‘Celtic.’

While not a Catholic football club, without Catholics, Catholicism and the Catholic Church in Scotland, there would be no Celtic FC. This fact is fundamental and pivotal to understanding the club’s origins, appeal, evolution, resilience and identities: and also in terms of understanding Devine’s aforementioned comment regarding Lisbon 1967 representing a defining moment in the journey towards the emancipation of Catholics of Irish descent in Scotland. Former Celtic footballer and manager, Tommy Burns, once commented that Celtic footballers had to remember that, ‘it’s more than just a football team they’re playing for. They’re playing for a cause and a people.’

Underdogs

For Celtic and its supporters, 1967 has become a moment when the underdogs in Scottish society became the most successful underdogs on the field of play. Some of the impact and meaning of Celtic’s victory in 1967 was expressed by

supporters and others during its 50th celebration two years ago. One said: “It was the best week of my short life. I made my First Confession on the 19th, Holy Communion on the 20th, Confirmation on the 24th and Celtic won the European Cup on the 25th. I was the centre of the world that week. When Tommy Gemmell scored the equaliser my two big brothers held me up and waved me about. Could life get any better?”

Another spoke of his encounters while attending the game in Lisbon.

He said: “What I remember was I kept meeting old school friends (I had left [school] only the year before). As most of us were Catholics and it was a holiday of obligation we headed for a church. There were a few old ladies in black, a few rich people with seats inside the altar area, and masses of Celtic fans with scarves and banners. The locals were totally bemused.”

One supporter who attended the match said, we were ‘no longer afraid to stand up and be counted.’ Ex-Celtic players and former Lisbon Lion John Fallon stated: “We changed a lot of attitudes for the good. We boosted the Catholics and the Irish.”

Heroes

Another fan said: “They were our heroes in a way that Muhammad Ali might be for black guys in America.” In 2017 one journalist added her own gloss while remembering the moment: “Theirs was a powerful beacon of achievement for an immigrant community that had been forced to deal with sectarianism and political marginalisation in Scotland.”

Lisbon 1967 does not exclusively belong to the Irish Catholic ethnic diaspora community in Scottish society. Nevertheless, what is certain is that Celtic’s European Cup victory loses its more meaningful significance unless examined in close relation to the history of this community.

To paraphrase CR James, when Celtic triumphed as European champions on what other occasion was there ever—among the Irish Catholic diaspora in Scotland at least—such enthusiasm, such an unforced sense of community, of the universal merged in a team of eleven (local) sportsmen or sportswomen? Celtic’s 1967 victory is not merely the story of a great sporting accomplishment—as extraordinary as it was and remains—it was, and remains, a landmark and an iconic moment in the social and cultural history of a country (Scotland) and a people (the Irish-Catholic diaspora) within that country.

Dr John Kelly is a Sociology of Sport lecturer at the Edinburgh University. Dr Joseph M Bradley is a Senior Lecturer in Sport at Stirling University and editor of recent new book Celtic Minded 4.