October 4 | ![]() 0 COMMENTS

0 COMMENTS ![]() print

print

The famous saints still winning over hearts and minds

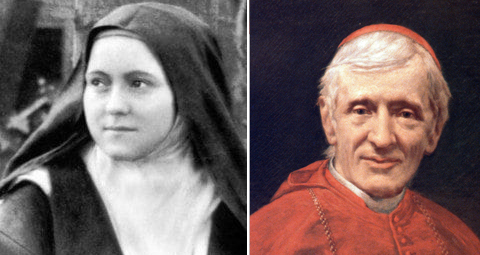

Dr Rebekah Lamb says St Thérèse and the soon-t-be-Saint Cardinal Newman have more in common than one might think, and argues that they can direct us to the freedom that comes through the truth of Christ.

IN her autobiography, Story of a Soul, St Thérèse of Lisieux says that Jesus granted her ‘the grace of penetrating into the mysterious depths of charity.’ We need look no farther afield than Scotland this past month to see how Thérèse’s ‘depths of charity’ have touched so many across this country in personal, local ways.

The visit of the relics of St Thérèse was very touching for me, personally, because this French mystic of the ‘little way’ is my family’s patron. Thérèse was a pivotal player in my parents’ conversion to Catholicism, which happened shortly after they were married and just as they were starting a family.

Looking back on the events that led to their conversion, my mum has joked that Thérèse started showering affection on them before they even knew who she was. Thérèse’s special love for my parents is one example, among countless others, of how God’s grace works in history: it comes in advance of our asking and often through the bonds of affection, of friendship, between persons, either side of the veil. Given all this, it was a special grace to be able to make a pilgrimage to Dundee to venerate her relics in early September.

Friendship

Thérèse possessed great insight into the spiritual dimensions of authentic friendship. Friendship is at the heart of her ‘little way’ and, at one level, Story of a Soul is a theology of friendship. For instance, towards the close of her autobiography, she says that she loves to ponder what full friendship with God, in the beatific vision, will be like.

Calling the beatific vision the ‘Eternal Face-Face,’ Thérèse says she longs to remind Christ that she has been his true friend, that she ‘manifested’ his name to those he gave her ‘out of the world.’ We also, of course, know that Thérèse longed for full union with God so that she could ‘spend’ her ‘heaven in doing good on earth,’ in continuing to build spiritual friendships with people in history, through the Communion of Saints.

The Catholic doctrine of the Communion of Saints presents to us the most radically transformative, expansive notion of friendship. It tells us that, through Baptism, all members of the Church are bound together. This doctrine has animated theological and artistic meditations on friendship, from the earliest days of the Church, onwards.

The Little Way

Thérèse’s theology of friendship, which she lived out in the hiddenness of a Carmelite convent in France, became one of the best, prophetic challenges to the emerging 19th-century philosophical ideas that all relationships are constituted by dynamics of power struggle.

That is to say, the ‘Little Way’ is the antidote to, and therefore also one of the best critiques of, the 20th-century ideologies of Fascism, Communism and our own prevailing ideologies that dehumanise the dignity of persons. Thérèse’s spiritual friendship with us since the 19th century is a reminder that agents of change, and authentic sources of meaning, within history are often found in the Communion of Saints.

As the Catechism of the Catholic Church reminds us, the Communion of Saints has a two-fold meaning. First, it is the community who shares in common the Sacraments and truth of the Church, of the ‘holy things (sancta).’

Sancti

Second, it is the community ‘among holy persons (sancti)’ who are adopted children of God through Baptism.

‘Holy persons,’ throughout history, have strikingly different personalities but one of the many things they share in common is a desire to intercede on behalf of others. Saints work within, and then far beyond, their particular historical moment, seeking out our good, praying on our behalf. They are both timely and timeless, belonging to history and eternity. They are examples of virtue and holiness who console and inspire us, reminding us that the deepest human bond within history is the Communion of Saints (the real social network, as it were).

If we survey history in light of this spiritual truth of the Communion of the Saints, we start to see very clearly that the saints are the key agents of divine providence. Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI says as much when he reminds us that if we are to look for the face of Christ on earth, if we wish to ‘track’ the movements of the Holy Spirit in history, we should get to know the lives of the saints, our friends, who witness to the revealed truths of the Church.

This witness, Pope Emeritus Benedict tells us, brings us into ‘close contact with the beauty of Christ himself.’

Beauty

The world of beauty ‘created by [the] faith and light that shines out from the faces of the saints,’ is the means through which Christ’s own beauty ‘becomes visible,’ he concludes.

People are moved to goodness by seeing concrete examples of it and, at one level, we can say that canonisation and the veneration of relics are ordained by the Catholic Church to, among other things, help us discern that history is not just some meaningless unfolding of technological progress, violence and power.

Rather, history is the dramatic unfolding of the providence of God, an unfolding that occurs through people, in specific contexts, and within the limitations of time, space and matter. The doctrine of the Communion of Saints provides us, then, with a new historical ‘sense,’ a way to discern this providence at work.

Christopher Dawson

The British historian, Christopher Dawson, wrote at length about this new Christian historical ‘sense,’ inaugurated with Christ’s entrance into history through the Incarnation. History, Dawson says, is the ‘process’ of continual ‘spiritual renovation,’ renovation that makes aspects of the unchanging, revealed truths of the Catholic Faith clearer over time.

Dawson especially understood saints to be those messengers of ‘renovation’ throughout history, who embody various aspects of the truth in the world. Importantly, Dawson’s sense of history’s religious character was especially shaped by decades of deep engagement with the thought of Blessed, soon to be Saint, John Henry Cardinal Newman, who will be canonised next week.

For Newman, history is the dramatic unfolding of divine providence in the lives of peoples and places, and the saints best give witness to, and discern, this reality.

God’s providence

A ‘holy Daniel’ or ‘Elijah the recluse of Mount Carmel,’ he says, can best ‘forecast the time of God’s providence among the nations.’

Newman liked to stress that the hidden lives of holy persons are often those that most fully reform and transform history. After all, Christ spent 30 years hidden in Nazareth, before his public ministry. And, to this day, in the Blessed Sacrament, Christ is that great respecter of human freedom, making himself radically but gently present to us by hiding in plain sight, under ‘the veil of sensible things,’ as Newman put it.

It is no accident that I opened with St Thérèse and have moved into a discussion of Newman. There are far more sympathies between the two than one might first think.

I am far from alone in suggesting this. As one example, for those of you who read the UK Magnificat, you will find in this October’s issue a beautiful, incisive reflection by its editor, Leonie Caldecott, on the importance of Thérèse and Newman as co-patrons for the renewal of the Faith in the United Kingdom.

Carmelites

She writes that in 1990 she ‘spent time at a centre in France run by secular Carmelites, called Notre Dame de Vie (Our Lady of Life),’ and it was ‘suggested’ to her that evangelisation efforts in the United Kingdom should be placed under the protection and patronage of St Thérèse and Newman, both of whom possessed missionary hearts and a deep care and concern for persons.

Caldecott shares that, in founding Second Spring: The Centre for Faith and Culture shortly thereafter, she took to heart the suggestion that ‘for the conversion of our country, it would take the intercession of Saint Thérèse of Lisieux and Cardinal Newman, working together.’

She also points out that in this month of October, this great ‘month of Mission,’ in which we have the feast of St Thérèse (October 1), Newman’s canonisation (October 13) and the feast of Newman’s conversion to the Roman Catholic Church (October 9), it is all too clear that the Holy Spirit is inviting us to look at the lives of these two saints in relation to each other.

In our increasingly relativistic culture, both Newman and Thérèse recall us to the reality that only the goodness, truth, and beauty of Christ sets us free.

In our increasingly commodified culture, both Newman and Thérèse invite us to imitate the humble, hidden lives of the Holy Family.

Encounter with Christ

In our increasingly isolating times (in which the British Parliament has even appointed a ‘Minister of Loneliness’), Newman and Thérèse remind us that we are not only called to friendship with others but to intimate encounter, and friendship, with Christ. These are reminders, for our specific historical moment, that the entire Church has been given, in unique ways, through the lives of Thérèse and Newman.

While it is important to think of Thérèse and Newman in relation to each other, it is also important, I think, that we pause to reflect on the significance of Newman, in his own right, for our times and especially for the current UK context.

This is because the saints of specific places and countries tell us something very significant about Providence’s work within, and through, specific cultures, traditions and peoples.

Of course, saints by nature transcend all earthly borders, regions and cultural difference. After all, French Thérèse ‘adopted’ my Canadian parents. But saints also inspire and shape local cultus (culture), devotional life and the spiritual sensitivities of specific peoples in specific times and places.

Holiness

Saints are global but they are also local gifts within history. Indeed, Newman himself stressed that the spiritual health and renewal of a nation depended, in large part, on its affection for its own holy men and women.

While living out his period of discernment in Littlemore, which ended in his conversion to the Catholic Church in 1845, Newman was working on a collaborative project, titled Lives of English Saints.

This project included short biographies and meditations on the personal histories of English saints as well as a liturgical calendar, featuring the feast days of England’s holy men and women.

In his Preface to Lives of the Saints, Newman says that having knowledge of, and affection for, ‘the saints of our own dear and glorious… yet most erring and unfortunate England’ will ‘serve us to make us love our country better, and on truer grounds.’ It will ‘teach us to invest her territory, her cities and villages, her hills and springs, with sacred associations; to give us an insight into her present historical position… and to open upon us the duties and the hopes to which that Church is heir, which was in former times the Mother of St Boniface and St Ethelreda.’

Newman canonisation

In this month of October, as Newman’s canonisation approaches, it is not just the global Catholic Church that is being invited by providence to learn from Newman. There exists a call and opportunity for the Catholic Church in the UK, in particular, to increase our knowledge of, and affection for, the life and thought of Newman.

In so doing, we will have better ‘insight into [our] present historical position,’ especially in relation to the nature of Church teaching, the development of doctrine, the call to find the truth (and the confidence we can find it), the links between revelation and our consciences, and the splendour of friendship with Christ (the only friend who, as Newman says, ‘can give us a tune and harmony,’ who can ‘form and possess us’).

I hope the large-scale and public reception of St Thérèse that happened here in Scotland so recently will be a precursor to, and indeed a model for, the same kind of devotion for Newman in his own nation, from October 13 onwards.

Dr Rebekah Lamb is a Lecturer in Theology and the Arts at the School of Divinity within the University of St Andrew’s.