July 12 | ![]() 0 COMMENTS

0 COMMENTS ![]() print

print

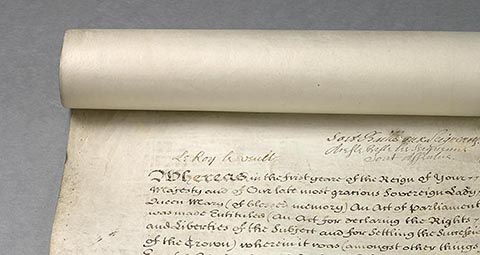

A constitutional Act of anti-Catholic bigotry

The Act of settlement bars Catholics from becoming head of state in the UK. James Bundy argues that an informed and pragmatic approach is needed to defeat the legislative discrimination.

The Act of Settlement 1701 is one of the most controversial, yet significant, components of the British Constitution (yes, the United Kingdom does have a constitution). The motivation behind the Act of Settlement, which bars Catholics from becoming king or queen, was to preserve the Protestant succession of the British throne.

In the 21st century, religion is no longer central to the political debate, but in 17th century Britain this was the norm.

To understand why the Act of Settlement was introduced, one must understand the political debate in England in the 1600s.

The Stuart monarchy believed in the notion of divine right of kings.

King James

King James VI & I (who reigned as King of England between 1603-1625) even wrote: “The state of monarchy is the supremest thing upon earth, for kings are not only God’s lieutenants upon earth and sit upon God’s throne, but even by God himself they are called gods.”

The notion of divine right was in contradiction to the standard practice of governance in England. It was already established convention that the King of England could not levy taxes without the consent of parliament.

King Charles I (who reigned between 1625-1649), however, governed according to his own conscience. This was portrayed as a tyrannical form of government which resulted in the English Civil War, Charles I being beheaded, and England becoming a Republic.

While the English monarchy was restored in 1660, suspicion surrounding tyrannical government was rife amongst the English population.

The underlying reasoning for this was its association with Catholicism.

Divine rights

King Louis XIV, a Catholic, was also a believer in the notion of divine right of kings and was centralising powers in France where he reigned.

As trivial as it may sound, absolute monarchy was one of the fears associated with a Catholic king.

Another reason why Catholicism was not popular among the English population was the failed gunpowder plot in 1605.

The propaganda of King James VI & I—the only serious news outlet at the time—was that it was a Catholic plot to kill the English king because he was head of the Church of England.

Fears of violence

Anglicans and dissenters therefore both viewed those who were Catholic as people who would resort to violence to convert the English people to Catholicism. It is within this atmosphere that historians must judge the reign of King James VII & II.

King James VII & II converted to Catholicism sometime between 1668 and 1672. This was while his brother, King Charles II, was still king. With England being a republic between 1649-1660, both Charles and James were brought up in continental Europe where their mother, Henrietta Maria, tried to convert both her sons to Catholicism.

His mother’s influence appeared to work for James’ Faith. Even before his conversion, James II believed in the real presence and called the communion service ‘Mass.’

Conversion

In today’s eyes it would not be a surprise when James II announced his conversion, but in 1670s there was panic. Anglicans and dissenters feared a ‘popish successor’ who would unite with the French army to convert his subjects to Catholicism.

These fears only increased when James II married the Princess of Modena, a Catholic. They increased again when the Princess of Modena gave birth to a son in 1688, confirming the Catholic succession.

Charles II was aware of the problems associated with Catholicism while in public office so sent the Archbishop of Canterbury and Winchester to try and convince James II of the ‘errors of popery.’ James II, however, was unconvinced and remained Catholic.

Test Act 1673

To try and stop the spread of ‘popery’ the English Parliament passed the Test Act 1673. Charles II—who converted to Catholicism on his death bed in 1685—gave the bill Royal Assent as he needed money to continue the war against Holland.

This act prohibited everyone from taking public office unless they stated that they did not believe in the act of transubstantiation. In other words, this was an outright ban on Catholics holding public office.

When James II became king, he had one objective: the equal treatment of Catholics and Protestants. James II saw the repeal of the Test Act 1673 as the first step of doing this. Parliament, however, refused to repeal.

This led to James II proroguing parliament and starting to use his prerogative powers. Anglican subjects accused James II of peculation and trying to restore absolute monarchy, while James II accused his subjects of sedition.

Even when it was clear that no progress was going to be made in improving the wellbeing of Catholics in England, James II continued to make the case as he believed in divine right.

Strong Faith

James II, in fact, believed that God approved of his regime and wished him to advance the Catholic cause. The belief that James II had in God and the Catholic Church has resulted in commentators concluding that James’ Faith was so strong that it surpassed human reasoning.

James II was so devoted to his Faith that he did not understand the fears the Anglicans had because he did not hear or see them.

The further James pushed his agenda, the more tensions increased amongst the dissenters.

Invasion

After an invasion in 1688 and the passing of the 1689 Bill of Rights, William III and Mary II were announced king and queen. Both were Protestants so the fear of a Catholic successor was removed.

Mary, however, died in 1694 childless. Without any intervention from parliament, the successor of William III would have been Anne—Mary II’s sister—whose heir was likely to be her Catholic half-brother: James Francis Edward Stuart.

Parliament stepped in to ensure that James Francis would not become king. They cited the reign of his father (James II) as proof that a Catholic king would endanger the Protestant faith.

1701

The Act of Settlement 1701 passed, and the new legislation clearly stated that no sovereign ‘shall profess the Popish religion or shall marry a Papist.’ This resulted in King George I (a Protestant German prince) succeeding Queen Anne, not James Francis Edward Stuart.

The Act of Settlement 1701, therefore, was introduced to protect the Anglican faith from Catholicism, which Anglicans feared would use force to convert them and establish absolute monarchy.

In the 21st century, these fears held by the Anglican church surely no longer exist which raises the question: Is the Act of Settlement still a requirement for the British constitution or is it time to repeal it?

Nick Clegg

In January 2013, the then Deputy Prime Minister, Nick Clegg, spoke about the Act of Settlement in the House of Commons: “The current rules of succession belong to a bygone era.

“They reflect old prejudices and old fears. Today we don’t support laws which discriminate on either religious or gender grounds. They have no place in modern Britain and certainly not in our monarchy—an institution central to our constitution, to the commonwealth and to our national identity too.”

Succession

This was during a debate on the Succession to the Crown Bill. This amendment to the Act of Settlement resulted in the eldest child of the monarch, rather than the eldest son, being the heir to the throne.

The bill also allowed members of the royal family to marry Catholics without losing their royal title, but royal family members and their children are still barred from practising the Catholic Faith.

Jacob Rees-Mogg

Speaking in the same debate, Jacob Rees-Mogg MP—a Catholic—stated that he ‘would happily accept no change at all, because that is the history of our nation.’

Mr Rees-Mogg, however, did argue that he was opposed to the amendment which allowed Catholics to marry members of the royal family but barred their children from being Catholic. Mr Rees-Mogg called this ‘an attack on the teaching of the Catholic Church.’

The most interesting aspect of Mr Rees-Mogg’s contribution to the House was what would happen if a Catholic was the heir to the throne. Mr Rees-Mogg accepted that there would be constitutional issues if a Catholic were to become sovereign as the Church of England ‘cannot be led by a non-member of that Church.’ Mr Rees-Mogg suggestion to overcome this obstacle was that a ‘regent would be appointed to take on the role of supreme governor of the Church of England.’

‘Pandora’s box’

Ian Paisley Jr MP argued, however, that the changes being proposed would open ‘a royal Pandora’s box of unintended consequences’ as ‘legislative changes will be required to no fewer than nine Acts of Parliament.’

In response, the late Paul Flynn MP argued that ‘there is universal approval in the House for the ending of gender discrimination, but does the minister not agree that the bill, rather than getting rid of a religious discrimination, actually reinforces it by excluding people from other religions—evangelical Christians, Catholics, Jews and Muslims—from the possibility of ever becoming Head of State?’

This debate, therefore, demonstrates the complexities associated with amending the Act of Settlement 1701. Ian Paisley Jr was correct when he stated that this change would lead to ‘unintended consequences’ as many pieces of legislation are underpinned by the Act of Settlement 1701.

Discrimination

Paul Flynn MP, however, was also correct when he argued that the bill of rights is religious discrimination as it bars people from becoming Head of State of their country due to their religion.

There are some Catholics like Jacob Rees-Mogg who will argue that we should respect history and leave the British constitution untouched. There are others, like me, who argue that times have changed, and our constitution should reflect that—but we should urge with caution.

Unlike King James II, we need to address the fears that those associated with the Church of England have with these proposed changes.

Debate

We need to come up with suggestions, just like Jacob Rees-Mogg did, about how the operation of the Church of England would change if the United Kingdom did have a Catholic monarch. The Church of England also has to debate these questions.

The Act of Settlement 1701 is religious discrimination against Catholicism. The parliamentarians who introduced this piece of legislation in 1701 would say so themselves due to the fears they had about Catholicism.

I hope that we can all agree—Catholics, Protestants and all other religions—that times have changed and the fears that people had about Catholicism should no longer exist.

Learning from history

Catholics, however, should learn from the history of our nation. When calling for the Act of Settlement 1701 to be amended to allow Catholics to sit on the throne, we need to address the concerns that those in the Church of England will have, and the impact it will have on the operation of the British state. Serious debate is required in parliament and dialogue between the Catholic Church and the Church of England is a must.

History indicates that changes to the British constitution must be slow. As unfair as it sounds, if Catholics demand too much too soon, then fears among people in the Church of England could rise and halt any progress towards religious equality.

I believe that it is time for the religious discrimination at the very top of the British constitution to end. Catholics must be allowed to sit on the throne, but to achieve this, we must take pragmatic and slow steps.