BY Daniel Harkins | May 11 | ![]() 0 COMMENTS

0 COMMENTS ![]() print

print

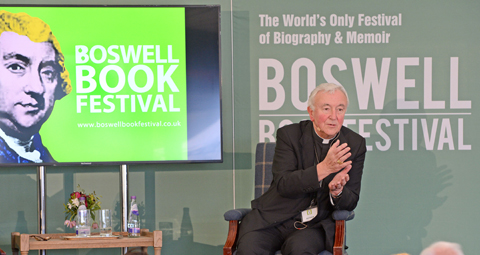

Cardinal Vincent Nichols on Alfie Evans, Brexit and divisions within the Church

DANIEL HARKINS speaks to the Archbishop of Westminster about his new book, religious freedom and the future of Faith in the West

Promoting a new book can be a tedious chore for authors, but for Cardinal Vincent Nichols, a trip to Scotland last weekend may have offered welcome respite.

The Catholic Church in England was at the heart of a tragic case that made headlines around the world last week. Alfie Evans, a 23-month-old boy, died on April 28 after spending more than a year in Alder Hey Children’s Hospital in Liverpool. His parents had fought through the courts for the right to keep their son alive, attracting support from Pope Francis, the Italian state and pro-life activists from around the world.

The courts, however, sided with the hospital, who wished to withdraw life support, arguing that continued treatment was futile. As protestors outside the hospital became increasingly frustrated, and amid threats of legal action against hospital staff, the English bishops affirmed their support for the hospital, and criticised those who ‘used the situation for political aims.’ It was a position that drew the ire of many, who saw in the Alfie Evans case a compassionless state overruling the rights of the family.

Speaking a week after Alfie’s death, Cardinal Nichols, the archbishop of Westminster, reflected on the case, and maintained that a child ‘is a gift, and not a possession.’

“One of the things which remains after this sad, sad story is that we have to find better ways of handling these whole procedures and look for ways of resolving conflict before they come to the ultimate arbitration of the court,” he said. “We need to look at how we hold the different important realities in place of a parent’s love and wishes and the reality of the best medical opinion, to try and find ways of mediating that will avoid what is inevitably an adversarial process in a court of law.

“There is a long tradition in Catholic teaching that we are not vitalists: we don’t have to take every last possible step to avoid the coming of death, especially when those steps are burdensome and, in the best judgment, futile,” the cardinal added. “And the second principal in Catholic teaching is clear that the child is a gift and not a possession and therefore there are limits on the rights of parents even though there are no limits on a parent’s love, and that is what makes [this situation] so terrible.

“A parent’s love is the strongest thing in the world. But it also needs alongside it clear, compassionate thinking and, for me, clear, compassionate thinking is an important practical expression of love and care.”

The Alfie Evans case seemed to illustrate an increasing polarisation of opinions in the Catholic Church. The aggressive, angry debate that has infected much of secular politics in recent years has crossed over into the Catholic sphere, as the papacy of Pope Francis divides the faithful down opposing lines. But the cardinal stressed that much of our news is conveyed to us through a media that has an ‘understandable desire to find conflict.’

“People who want to probe what the Pope is saying are immediately cast as opposed to the Pope: it has happened to me occasionally. There is a lot more holding us together and holding us in a single mission than there are searching questions and challenges,” he said, adding that ‘one of the things that really dismays [Pope Francis] is idle gossip and some of the ways social media is used irresponsibly.’

Some within the College of Cardinals, notably Cardinal Raymond Burke, have been combative in their criticism of Pope Francis’ liberal reforms. But Cardinal Nichols said that while the Holy Father ‘gives people space to speak their mind,’ he is ‘not the type of man to respond to every question tossed to him.’

“Being Pope isn’t a question and answer session; it’s setting a direction and being committed to that direction,” he said. “It’s a little ironic when people appear to criticise the Pope on the basis of their own authority.

“The great gift of the papacy in the Catholic Church is that it is an expression of the authority of Christ, which is not a book and not a theory—it is a person and a person that can say yes and can say no to you. And in that sense it is very incarnate. Just as the Word of God is primarily a person in Jesus, so too the authority in the Church is primarily a person in the bishop, the Pope.”

Cardinal Nichols was ordained a priest in 1969, was made an auxiliary bishop of Westminster in 1992 and a cardinal and Archbishop of Westminster in 2009.

Over those decades, the Church has declined sharply in the West. One solution proposed to this problem, the so-called Benedict Option, is for Christians to withdraw into local communities. But the cardinal warned against ‘creating a defensive barrier around Faith’ or ‘seeing ourselves as besieged.’

He said there is ‘not one model’ for Christian living, and pointed out that living a Catholic life in Poland is very different to doing so in the Highlands of Scotland, which in turn is different to the middle of London.

“It’s part of the job of the Church to create an ecology in which Faith can breathe and generate and prosper,” he said. “For most Catholics that begins in the parish; for many it begins in their family. And these are the ecologies that nurture Faith. Sometimes an ecology needs a greenhouse, a protection from other elements, but sometimes it doesn’t.”

Seeing ourselves as besieged or living in a radically hostile environment, the cardinal added, will ‘not lead to a strengthening of Faith.’

He said that while there are areas where Christianity survives in hostile environments, even in those places there are ‘ways in which society breathes together.’

Faith Finding a Voice, the cardinal’s new book, gives one example of such a place. Gaza has a tiny Catholic population of a few hundred, living in one of the most volatile places on Earth. But the parish has a primary and secondary school, and a nursery for abandoned children.

“All of those bring that Catholic population together,” the cardinal said. “When you find a common good, when you find what is good for the human being and begin to serve that explicitly in the name of Christ, then you are not living in a fortress, you are living in a shared space.”

While the cardinal recognised the rise of secularism in the UK, he stressed that we do have ‘considerable freedoms in this country.’ He said: “We have to learn not to look at the privileges we might have lost but at the reality before us and how in these circumstances we can act and speak attractively to draw people to Christ,” he said. “If we can’t manage to portray Christ as an attractive person then we are not serving him.”

Though UK society may be increasingly rejecting Christianity, Cardinal Nichols believes the Church can still serve as its conscience.

“I don’t know about you but sometimes I’m troubled by my conscience and the idea that a society might feel a bit uncomfortable before the principles and the message of Christianity is a good thing,” he said.

“That’s not unsurprising—in fact if it didn’t then we are too comfortable and somehow the edge has gone off our conscience.

“There are lots of very difficult issues where we should attempt to be the conscience of society—and not to be offering solutions all the time.

“The Church and its message of the Gospel is not a place where ready-made solutions to complex problems are found, but it is a place in which principles and the light of revelation can help with complex issues that have to be tackled.”

Cardinal Nichols’ archdiocese is the centre of political power in the UK, and his time as archbishop coincides with a period of great change in the country’s relationship with Europe. The cardinal however stressed the need for the UK not to see itself as ‘withdrawing from the world.’

“My archdiocese has people from 30 different nationalities—that’s the reality,” he said. “The world is here. We live in a single world, a globalised world, with all its difficulties.

“As a Church we are clear that we don’t withdraw from Europe. We are fully participating in all the European connections and shared endeavours. There are issues, maybe, about the European Union but we are not withdrawing from the world; the world is on our doorstep.

“It’s that defence of always being part of a universal Church that is the great characteristic of the Catholic identity. That comes right through now, past all the division of the Reformation, past all the nationalising tendencies of the Reformation, and remains the appeal of the common body of human beings called to worship God in and through Christ in the universal Church.”

– Cardinal Vincent Nichols was launching his new book Faith Finding a Voice (Bloomsbury, £12.99) at the Boswell Book Festival.