February 23 | ![]() 0 COMMENTS

0 COMMENTS ![]() print

print

Scotland’s anti-Catholic riots: violent 18th century attacks aimed at saving a ‘Protestant state’

In the first of two articles looking at the repeal of anti-Catholic legislation, MICHAEL TURNBULL explores the riots that hit Edinburgh, the crusading Bishop Hay, and the explosive language that whipped up bigoted sentiment and led to violence - By MICHAEL TURNBULL

No one was more involved in organising Scottish opinion to repeal anti-Catholic penal laws in the UK than Bishop George Hay. Born in 1729, Bishop Hay was coadjutor vicar apostolic of the Lowland District—a large half of the country lying below a diagonal line drawn from Glasgow to Banff on the Moray Firth. Bishop Hay, who was born an Episcopalian, had trained in Edinburgh as a surgeon and as a student had helped to tend the wounded at the Battle of Prestonpans in 1745.

He followed Prince Charlie’s army to England where he was captured and imprisoned. During his imprisonment he converted to Catholicism.

On May 14, 1778, Henry Dundas, MP and Lord Advocate for Scotland, confirmed the government planned to introduce a bill to alleviate the penal laws against Roman Catholics in Scotland, legislation already in the final stages of enactment for Catholics in England. Royal Assent was given to the English Catholic Relief Act on June 3, 1778.

Bishop Hay had been heartened by the new English Catholic Relief Act and drew up a series of proposals by which the ‘old sanguinary’ laws governing Scottish Catholics might be relaxed. This included the repeal of laws against ‘sayers and hearers of Mass’ and the repeal of a statute preventing Catholics from holding property.

Catholics, urged Bishop Hay, should be permitted to be Freemen in burghs, but without votes in elections. Military and naval commissions should also be open to Catholics, provided they took a test-oath affirming their attachment to the King.

He hoped that Catholics, upon taking the oath, might be allowed once again to qualify and practise as lawyers, attorneys and physicians and called for an interim toleration for the exercise of the Catholic religion in private.

Bishop Hay’s proposals were put in detail to a meeting of Catholics in Edinburgh on September 10, 1778.

Two days later, representatives of the Highland Catholic community also joined the discussions in Edinburgh. They confirmed that, as proof of their loyalty to the government, to the constitution and to the settlement of the crown of Great Britain, their people had already done everything possible to support the recent military levies in the Highlands.

Under the penal laws Catholics serving in the British armed forces faced religious discrimination. Bishop Hay pointed out that in the war with France, the two Highland battalions, which had made such an effective contribution to British victories in America, were to a great extent made up of Catholics—both officers and privates.

Bishop Hay complained about the treatment that they and their fellow Catholics were subjected to in the services—and the fact that even the occasional exercise of their religion was forbidden.

In its assemblies and synods, the Church of Scotland provided a platform for the expressions of unease and even outrage which some members of the Church felt at the thought of the repeal of the penal laws in Scotland.

The influential synods of Glasgow and Ayr met on Tuesday October 13, 1778, and resolved to oppose the extension of Catholic relief to Scotland.

Although the synods were careful to describe their opposition as only including lawful means, like a pebble thrown into a lake, their views had their effect.

On October 18, a Sunday, a group of Catholics met in the Glasgow home of Donald McDonald, a Highlander.

Beginning at noon and over the next hour, a large hostile crowd assembled outside McDonald’s house. As the worshippers were preparing to leave some of the protesters broke in. According to reports, ‘they threatened to tear the Catholics limb from limb,’ while others shouted out against Popery and demanded to see the crucifixes and statues. A volley of stones followed. Then the house was looted—doors torn from their hinges, furniture broken open and ‘everything taken away.’

Soon after, a report by a member of the synod was sent to The Glasgow Mercury and published on October 22.

The writer stated that the synod had considered ‘the growth of Popery… whereby they become an easy prey to Popish emissaries, and are seduced into that detestable superstition, whose distinguishing doctrines, and usages are according to the flesh, after the working of Satan, in all the deceivableness of unrighteousness… That cruel superstition, which has often been drunk with the blood of the saints… which, the more it advances, the more powerfully it operates in pulling up the foundations of a Protestant state.’

The Synod of Dumfries met on October 21 and instructed their moderator to write to the Lord Advocate requesting him to prevent the repeal of the Scots acts of Parliament against Popery.

On December 3, 1778, after several weeks of mounting anti-Catholic agitation, Bishop Hay became vicar-apostolic of the Lowland District. That January, tensions were high at the possibility that the new Catholic Relief Act was also to be applied north of the border. This legislation passed by the Parliament of Great Britain freed Catholics in England to own property and inherit land.

Scottish Protestant condemnation and anger boiled over. Highly charged statements filled the press in what seems to have been a well-orchestrated campaign.

From Bishop George Hay we have eyewitness accounts of the disturbances in Edinburgh in early February 1779, written a week later. He begins by saying that Roman Catholics had been forced to stay indoors as their appearance in the streets of Edinburgh would be met with calls of ‘Here is a papist, there is a papist, knock him down, shoot him.’

On January 30, a Saturday, a mob composed of a large number of people gathered around his newly renovated and reconstructed house in Trunk’s Close, on the north side of the High Street. The rioters broke his windows and continued to inflict damage until late at night.

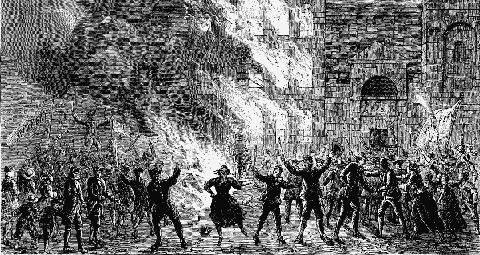

The next day, a call to action filled the city warning that one of the next three days had been agreed upon for the burning of the bishop’s new house and for the destruction of the old house and Catholic chapel further up the High Street at Blackfriars Wynd, along with the houses and shops of the chief Catholics in the burgh.

The following Tuesday, February 2, was the feast of Candlemas and, about midday, the mob gathered again around Bishop Hay’s newly constructed house, throwing stones and other objects at the windows and at his servants.

By two o’clock the situation had deteriorated to the extent that the two priests inside, Fr Cameron and Fr Mathison, had to get up in the middle of their meal and see to their safety.

By now, the stones and missiles were being thrown so hard and repeatedly from every direction that they had to get out and flee to another house.

The mob soon returned to Bishop Hay’s new property in Trunk’s Close. They attacked the outer door with stones and hammers. They forced the doors and in a moment the house was full of rioters. Using stones and hatchets, they began breaking all the doors, cupboards and drawers.

By now a huge crowd had surrounded the house and all its approaches. The cry went up to set fire to it immediately. Straw, tar barrels and other combustible materials were placed in all parts of the house. Before 10 o’clock that night, the whole house and most of the furniture, which belonged to the five families that lived there, was reduced to ashes.

The mob expressed their delight with shouts of glee—their only regret being that they did not have one of the priests to throw into the flames—little knowing that Bishop Hay had arrived back from London during the height of the destruction.

– Next week: part two focuses on the anti-Catholic riots that tore up Glasgow.