March 10 | ![]() 0 COMMENTS

0 COMMENTS ![]() print

print

Hidden history of British Catholic life

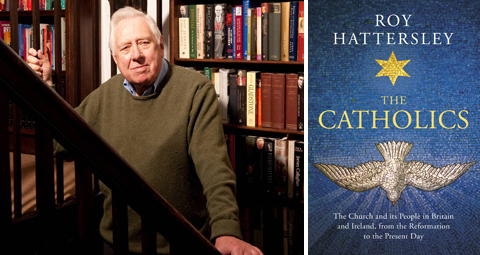

He may not be religious but Roy Hattersley’s latest book explores the Church and its people in Britain and Ireland from the Reformation to the present day. RICHARD PURDEN talks to the 84-year-old peer and former deputy leader of the Labour Party

LABOUR party big beast Roy Hattersley served in Harold Wilson’s government, Jim Callaghan’s cabinet and was deputy leader of the party from 1983 to 1992. He has previously written 25 books and his latest work, The Catholics, explores the Faith and its people in Britain and Ireland from the Reformation to the present day.

Significantly, the author’s father had served in the priesthood before leaving to marry Mr Hattersley’s mother. “I didn’t know he had been a priest until he was dead; the bishop of Derby wrote to tell me about it,” he confirmed down the line from his home in Derbyshire on a fresh February afternoon.

Although the former parliamentarian is not a Catholic himself, I wonder if religion has played a part in his life.

“My mother was asked that question when I first joined the cabinet. She said ‘we had no religion—we were Church of England.’

“I’ll get into great trouble for saying so but it was a la carte, take what you want and leave the rest. There was wriggle room for people who were not sure what they believed. The strength of the Catholic Church is its certainty; you have to get it right or get it wrong.”

The blurb on Mr Hattersley’s book suggests the ‘survival of Catholicism in Britain is the triumph of more than simple faith.’

While the author is not a Catholic, nor religious at all, he admits: “It’s a good story and one that hadn’t been written before.

“It struck me how Catholicism survived and how the story has heroes, villains, treachery, devotion and sacrifice—everything a good adventure story should have.”

Undoubtedly there is a sense of that adventure when reading of the previously unpublished instructions given to Jesuit priests on how to evade capture. “They had permission to wear disguises and deny their Faith rather than be kept in a court and executed—that was one piece of previously unpublished material.

“There was also a snide letter written by Cardinal Newman complaining that [Augustus] Pugin was undermining the Catholic Church.”

I ask him about a passage on the Pope calling for the assassination of Queen Elizabeth I. “Elizabeth’s purge was more brutal than Henry. The Pope said a good Catholic was entitled to and should murder her.” The Catholics also looks at how the Reformation impacted Catholic life here and across the border. “The English Reformation was about power and the Scottish Reformation was about ideas; it was much more intellectual. Merchants came to the East Coast ports of Scotland and brought with them Luther’s ideas, then the Kirk got hold of them.

“They had a hold on people that the Catholic Church couldn’t compete with, but residual Catholicism remained.

“It wasn’t until 19th century with Irish immigration that Catholicism flourished again.” Further to that, Mr Hattersley examines the experiences of those Irish Catholics coming into various parts of Britain such as Liverpool and Glasgow.

What life had once been in Ireland proved to be a very different prospect in Britain.

“They came to do the worst jobs in the poorest conditions for the lowest pay. Many women turned to prostitution as a way of making a living for their families—there’s no doubt that it happened. In Ireland they had been impeccably moral but in the slum conditions in which they lived, they were forced into it.” Hostility came in various forms and manifested among fellow Catholics and other Christian denominations.

“Irish immigrants were not popular and certainly people spoke openly about the threat of Irish Catholicism.

“They were seen as insurgent rebels on the side of France and Spain against England. They were also unwelcome in Britain by the indigenous Catholics. In Ireland, Home Rule and independence was a religious manifestation of Catholicism, even though there were some Protestant leaders such as Parnell.”

Irish Catholics arriving in Britain after the famine suffered further with racial intolerance. Mr Hattersley’s book cites a pamphlet published by the General Assembly of the Free Church of Scotland—The Menace of the Irish Race to Our Scottish Nationality—and the writings of GR Gair of the Scottish Anthropological Society, who published a series of articles which ‘explained’ the cultural and psychological differences between the Irish and other ethnicities.

Mr Hattersley suggests one common and bigoted perspective was ‘the Catholic poor wanted to be helped and the Protestant poor helped themselves.’

“The Catholics in Glasgow and Liverpool were in a terrible situation and they did their best in those hideous circumstances; those who did survive deserve credit.”

Beyond surviving the Irish Catholic community began to settle in Scotland, leading to a unique diaspora culture and ethnic identity. As Mr Hattersley suggests, it took some time for the community’s needs to be met but a major victory and chief concern was Catholic education. Strength and security was gained in forming clubs. It was there the Irish could gather a sense of themselves and how far they had come.

Mr Hattersley suggests groups such as the Catholic Young Men’s Society were ‘very important.’ He added that Catholics are ‘at their strongest when in groups, and these groups strengthened their resolve.’

“In Scotland it helped keep the Church together—in smaller towns and numbers they were inclined to lose Faith.”

The former Labour deputy leader suggests it was necessary for supporters of Hibernian and Celtic to join Catholic societies for spiritual sustenance and fortitude.

“The community clung together in groups. It made them feel more comfortable and wanted; football became a big part of that.

“One of Celtic’s first patrons was Archbishop Charles Eyre. For the Church in Scotland, football was an obvious way of galvanising the community.”

Mr Hattersley, a passionate Sheffield United supporter, was once commissioned to write about supporters on both sides of the world-famous Glasgow football derby. “I was asked to write about the [Glasgow derby] for The Herald.

“The editor was reluctant to let me go into the crowd in case I got bashed about, but I went in and they were very friendly. The animosity was artificial.

“They [Rangers fans] didn’t really want to be ‘up to their knees in Fenian blood.’

“I spoke to a couple: one had a mask of Margaret Thatcher and the other Saddam Hussein. He said ‘I’m Celtic and she’s Rangers.’

“I think we have to be tolerant of each other but we also have to mind our language—it’s not polite to be offensive.”

Before signing off, the former Labour MP suggests that ‘there’s more Catholics than any other one religion in Scotland,’ citing an article in The Scotsman which suggests this is due to Polish immigration. Today it’s estimated that around 61,000 Poles now call Scotland home, and many of them have helped to grow diminishing congregations, increased the numbers of those entering the clergy and allowed the Church in Scotland to flourish in the 21st century. Mr Hattersley suggests that ‘affluence and education’ has eroded belief for many.

“What people want is freedom to say and do what they want—and that is a challenge for the Church,” he says.

Perhaps when seeing a relatively new community struggle to assert itself and establish roots we are reminded of own history, maybe even a deeper truth, and a more resonant freedom.

Roy Hattersley is appearing at the Mitchell Library, Glasgow, as part of the Aye Right! Festival on March 15. Tickets £10.

The Catholics (Penguin hardback, £25) by Roy Hattersley is out now.