August 31 | ![]() 0 COMMENTS

0 COMMENTS ![]() print

print

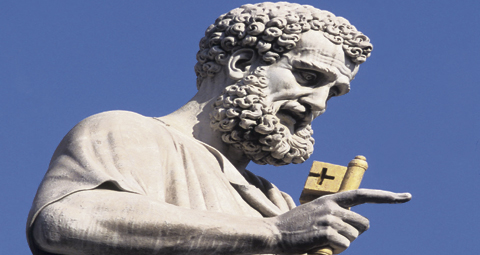

Unmasking the men at the heart of the Church

— Dr Harry Schnitker, in his new series on the history of the Papacy, gives an introductory insight into those, good and bad, who have sat in St Peter’s Chair

There are many ways in which one can define Catholics. We are, of course, first and foremost Christians, followers of Jesus. We have a distinct prayer culture, heavily marked by a devotion to the saints, and in particular to the Virgin Mary. As Catholics, we have the received teaching of the Church, both from Scripture and tradition. Yet if one were to ask non-Catholics what is the most obvious iconic symbol of Catholicism, the answer would be the Pope.

Organisationally, it is indeed our allegiance to the Holy Father that is the unifying element of our Church, that defines us as Catholics. This has long been recognised, and is frequently summed up by the epitaph ‘Roman’ when the Catholic Church is mentioned. ‘Catholic’ derives from the Greek καθόλου or ‘kath’holou, which signifies ‘in general.’ From this came καθολικός or ‘katholikos,’ which means ‘universal.’ A Church calling itself ‘Catholic’ is, therefore, a universal Church.

This is how we see ourselves, even if there is some tension between the local and the international at times. We are a global Church, or, to be precise, the Global Church. Yet for that to be true, we also need to have a focal point, a centre, something that binds us together. Of course, in a theological sense, these ties are metaphysical. We believe that we are the Body of Christ, and that the Spirit moves within our Church.

However, we should recall that division is the norm. Even in the earliest days of the Church, St Paul was writing to the Corinthians to admonish them for the divisions amongst them (1 Corinthians 1:10 to 4:21). In the Eucharistic Prayer, we ask for unity, and make it explicit that this unity is expressed through our union with Rome.

That Rome is our focal point has a number of historical reasons as well as a theological one. Theologically, it is the result of the incumbency of St Peter as the first bishop in what was then the Imperial capital. The ‘Prince of the Apostles’ was explicitly singled out by Jesus to head His new Church; after the Apostle professed Christ to be God, Jesus replied: “And I tell you that you are Peter, and on this rock I will build my Church, and the gates of Hades will not overcome it,” (Matthew 16:18). Famously, Jesus played upon the meaning of Peter’s original name in Aramaic, for Cephas means Rock.

Such is the importance of that statement that the Church coined the phrase Ubi Petrus, ibi ecclesia: Wherever Peter is, there is the Church. There is a snag. St Peter was not only the first Bishop of Rome, he was also the first Bishop of Antioch. That leads us to the historical reasons for the centrality of Rome to our Church. Originally, the Church grew to become united around a number of major urban centres. These included Jerusalem, although that lasted only to the Roman destruction, Alexandria in Egypt, Antioch in Syria and Rome. Later, Constantinople was added to this number.

The bishops of these sees were known as patriarchs, and were regarded as the leading voices amongst the bishops. The Catholic Church holds—and I believe on good historical grounds—that the Bishop of Rome, the Pope, held primacy amongst the patriarchs from the start. Now there are several instances from the very early years of the Church where one can point to bishops turning to Rome for a verdict. Perhaps the most telling is the exchange between St Polycarp, Bishop of Smyrna —now Izmir in Turkey—and Pope St Anicetus about the dating of Easter, in which the Martyr-Saint of Smyrna clearly defers to the Papal view.

The Pope, then, was a primus inter pares, first amongst equals, and this is how the Orthodox Churches still regard the See of Rome. In the West, however, there were no equals. The Roman See, placed in the capital of the Empire, and founded by St Peter, was the source of authority. The man who was its bishop was necessarily the sole source of teaching and the centre of the Church.

As the contacts between East and West waned as the Medieval period developed, the position of the Pontiff became unassailable. Indeed, by the early 12th century many of the Western Crusaders could not conceive of any other source of authority, and nor could they contemplate Christians whose practice varied from that of Rome.

Does that mean that the primacy of the Roman See has no base in reality? That is a difficult question, and sits at the heart of the discussions between the Catholic and Orthodox Churches on an end to the schism. From a Western perspective, the See of Rome is the only real source of teaching, and unity with Rome essential if one is to be part of the ‘Catholic,’ that is to say the global, Church. Many in the East share that view. This gave rise to the various Oriental Rite Churches united with Rome. Indeed, many Protestant churches define themselves vis-à-vis Rome, having come into existence in protest against the Papacy.

There is, in other words, a definite reality to Rome’s pre-eminence. Over the centuries, that pre-eminence has waxed and waned. Sometimes that was the result of historical development. Roman prominence grew after the conversion of Constantine, waned as the Germanic kingdoms of the Early Middle Ages grew in power, waxed again under the Carolingians, only to fall into almost obscurity as Charlemagne’s great empire collapsed. It bounced back under the great reforming Popes of the High Middle Ages, to reach its European zenith during the Pontificate of Innocent III.

A slow decline set in, followed by the great scandal of the Avignon exile, and the moral swamp in Rome that contributed greatly to the Protestant Reformation. From this grew the energetic Church of the missions to the rest of the world, of the Jesuit Order and the Baroque, which in turn slowly declined until smashed by the French Revolution.

Having virtually vanished over large swathes of the European Continent, the Church experienced a great flourishing in the 19th century, which continued in spite of the loss of the Papal States until after the First World War. This was the time of the African and Asian missions, when the Church reached all corners of the globe. More recently, the Church has tried to come to terms with gigantic social and global shifts, which has seen it severely retract in much of Western Europe, but expand exponentially elsewhere.

During all these cycles of growth and decline, punctuated by numerous crises, the role of the man who occupied the Chair of St Peter has been very important. Some very able Popes steered the course of history. We shall meet several of them in this series, but for now the mention of such names as St Sylvester, St Leo the Great, St Gregory the Great, St Leo III, St Nicholas I the Great, St Gregory VII, Innocent III, Paul III, Leo XIII and Blessed John Paul II the Great should be enough to whet the appetite.

I do not, however, intend this series to be a panegyric. There have been some Popes that can only be described as dreadful, whose actions both morally and ecclesiastically are beyond belief. There have also been a large number of Pontiffs who muddled along as best they could. The Papacy very rarely has had real power, that is the power of violent coercion. In most instances, the only weapon a Pope had is that of persuasion and moral standing. Sometimes these were simply not sufficient.

In this new series, then, we shall encounter some of the men at the heart of our Church, placed against the background of the two millennia that have passed since Our Lord spoke those words to St Peter. At the end, I hope that the reader will have gained a deeper understanding of those words. For it is surely providential that over that huge passage of time the Church has managed to survive and flourish, sometimes in spite of the incumbent of St Peter’s Chair, and sometimes steered by the Popes.