September 9 | ![]() 0 COMMENTS

0 COMMENTS ![]() print

print

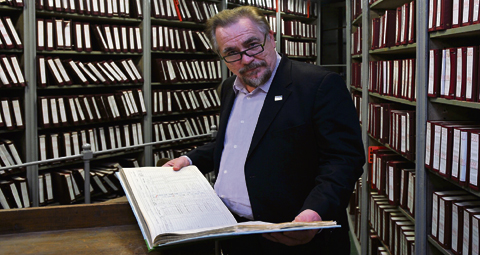

The Celtic journey of Brian Cox

In a special feature, Richard Purden speaks to Scottish actor Brian Cox about his life and work and how both have been shaped by his Irish Catholic roots in Dundee

After training in London, Scottish actor Brian Cox established himself treading the boards with both the Royal Shakespeare Company and the National Theatre. Today, a well known Hollywood and television actor, he’s appeared in popular and cult films such as Manhunter, Rob Roy, Braveheart, Rushmore, X2 and Troy.

Born in Dundee with Irish Catholic roots, the actor has been fundamentally shaped by the Celtic blend of his Irish and Scottish family tree. His great grandfather left Ireland during the Great Hunger, just as Scotland was going through a massive industrial shift. As a character actor the study of his Irish family background and their journey proved to be an essential inspiration for the Scot throughout his life.

“I’m 100 per cent Celt in fact I’m directly related to the progenitor of the High Kings of Ireland, Niall of the Nine Hostages,” he said. “My great grandfather came from Fermanagh just outside Enniskillen, Cox is an anglicised version of a Gaelic name; it was easier for the English to keep track of Irish subversion by changing the names. My family was quite large and they owned two fields but the two fields couldn’t support a family. My great grandfather was a qualified stone mason, also I think he was probably an inerrant worker and came to Scotland for the seasonal work on farms digging up potatoes and picking berries sometime in late 19th century. When the Great Hunger hit his parents became quite ill and died. He married a woman called Bridget Bolan and moved to Dundee to work in the Jute Mills. It was around this time little Irish ghettos started forming in Dundee.”

For Mr Cox a point of interest is the Celtic meshing between the Irish and the Scots as well as their religious difference. Post war the offspring of that Irish influx had a less obvious expression of their background. More important than an ethnic identity was a strong relationship to the Catholic Faith and to Scotland.

“My family would use the old word; they would say they were Scotch,” he said. “My mother was called Molly McCann and you can’t get a more Irish sounding name than that but they insisted we were Scottish first and foremost. What went on in Dundee was a curious transformation, it was a more integrated society, and we didn’t have the problems that you would associate with the North of Ireland and the stuff that drifted into Glasgow. Dundee was more of a feudal society, it was the home of an immensely right wing paper but there was more freedom of movement, paradoxically there was a yin and yang to the place.

“There’s a Celtic journey that goes on and this particular journey from Ireland to Scotland manifests and exists between the polarities of Catholicism and Presbyterianism. I love Ireland and I love the language, they are charming, they are funny and they are the best story tellers but one benefit from our journey to Scotland is that we learned how to say no. It’s fascinating that the Irish don’t have a word for no; an Irishman would rather cut your throat than say no to you. It’s a curious psychosis in the mentality.”

I asked him if there was a sense of your ancestors coming from Ireland played down?

“It was rationalised but not in terms of our Faith,” he replied. “My first Confession was on a Friday, my first Holy Communion was the Saturday and I was confirmed on the Sunday. It was a weekend event.”

Today a relatively new flowering of Irishness in Scotland continues to gain momentum. For previous generations the expression was confined to St Patrick’s Day.

“March 17 was a very interesting time because then we suddenly became Irish and wore shamrocks, the rest of time we were Scottish but on St Patrick’s Day we (Catholics and Protestants) knocked hell out of each other, it was done in a very little boy way and then it was over; we were the best of friends again,” he said. “The community was mixed, most of my pals were Protestant kids and I became fascinated by the Protestant work ethic and I embraced that, I think we’ve both learned much more with the towing and throwing between the cultures.

“The Irish brought the sense of celebration which was very important culturally; it broke the confines of Presbyterianism. On a Monday the Catholic family would burn the coal; there would be raging fires and at the end of week they would freeze, the Presbyterian way was to eke the coal out.”

A vital difference for the actor was the visibility of women in the Catholic Faith, that artistic and cultural expression is what Mr Cox believes challenged the patriarchal and at worst misogynist characteristics of Scottish life.

“To me the virgin is one of the iconic images of childhood, the female is the image of nourishment, protection and love and it is very important in the Catholic Faith; that wasn’t present for the Scot,” he commented. “Catholicism is all about doubt and questioning where Presbyterianism deals in certainty and absolutes.”

Undoubtedly most Catholics would be familiar with a sense of the matriarch, historically the culture around work in Dundee for Catholic women similarly placed the wives and mothers as the breadwinners.

“When my family arrived in Dundee it was mainly female work in the Jute Mills, spinners and weavers,” he said. “I think that is where the idea of the indolent Irish worker came from, which is a myth because suddenly you had all these Irish farmers in a new environment. I’ve always thought it was a curious coincidence that the need for labour in Britain happened at the same time as the Great Hunger. Was the potato poisoned? Suddenly the Irish influx all over Britain in places like Lanarkshire and Liverpool were functioning with a much needed Irish workforce.”

In interviews Mr Cox has been particularly forthcoming about his Irish Catholic background and Celtic identity. Far from being a hindrance it’s given him a certain confidence and context.

“In the US a lot of people think I’m English, you find the Irish American identity is very forthright but I’m as Irish as they are,” he said. “I’ve never had any problem with it, the thing is before people weren’t interested in the whole idea of roots, as an actor it’s the creative part of what you do; that’s where you start from, so you’ve got to discover who you are. There’s a whole culture of it now with Who Do You Think You Are? and Ancestry.com; people are waking up to it. Things have changed in the most amazing way. My mother used to talk about starting from the year dot, it was about starting where you were born and you dealt with that; you dealt with the life you had to keep you sane and not get carried away.”

Over the years, Mr Cox has played many Celts from a variety of backgrounds. Most recently he took on the role of former Speaker in the House of Commons Michael Martin. Baron Martin of Springburn was the first Catholic to serve in the role since the Reformation but was forced to tender his resignation after a much publicised expenses scandal. Significantly Mr Cox remains sympathetic towards the man he portrayed in the BBC drama On Expenses.

“I could understand the character in many ways, we’re of a similar age; he is a working class man of Catholic tradition,” he said. “I think he’s a good man but he got a bit caught up in the pomp and circumstance of the house. A Pandora’s Box had been opened and he couldn’t put the lid on it; he became a patsy and that was shameless. He needed help and support and didn’t get it so he reverted back to his old working class trade union past. I don’t think that was right for the situation; you have to be more of a bobber and weaver; he’s not that canny in terms of PR. The problem was he would just lose his temper and start talking rubbish… but he was on the ropes by that stage the poor guy.”

By his own admission Mr Cox lives something of a nomadic existence, as our interview draws to a close he makes his way towards two large holdalls pitched in the Georgian hall way of an old Edinburgh town house, before making his way back to Dundee prior to another Atlantic crossing. For Mr Cox this life is just another expression of his Irishness.

“I think that’s part of being an Irishman and part of being a Celt; we do drift and we don’t get settled for long because we’re still searching and trying to find where home is,” he remarked. “I think we are almost homeless in that regard I’m as homeless as I ever was; I still don’t know where I’m from. My feeling is the world is not changing quick enough; people still get caught up with their little domains, as soon as you have a home then that you create the rules of the home. I’ve always wanted to be a part of that wanderlust thing.”